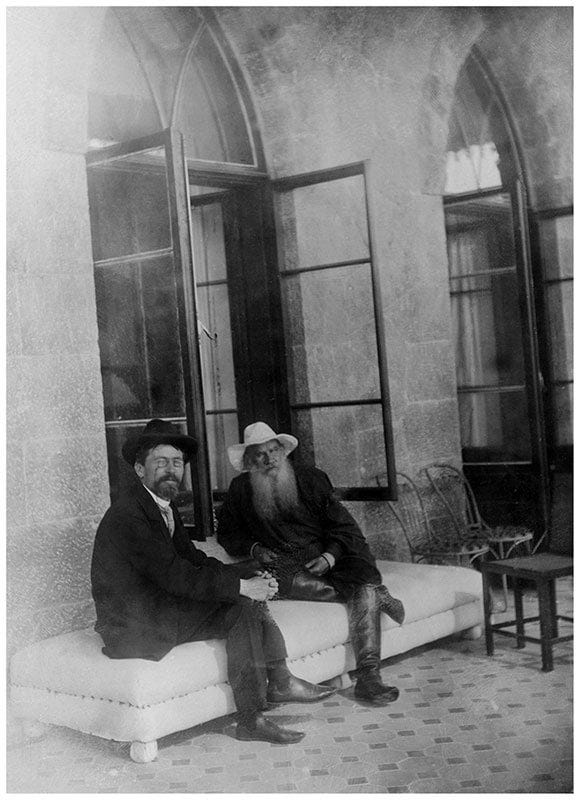

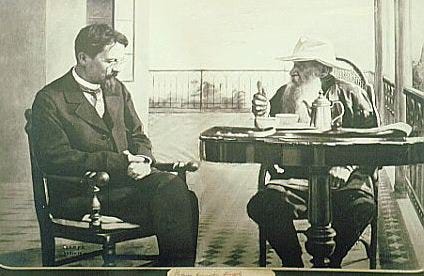

An exercise in literary ventriloquism between Chekhov and Tolstoy

Translation of memoirs, letters, diary entries: 99% organic, 1% apocryphal

When Anton Chekhov died on 15 July 1904 in the distant German town of Badenweiler at the age of 44, having suffered from tuberculosis his entire life, the 76-year-old Tolstoy was profoundly shocked. In his diary, he wrote of an irreplaceable loss to Russian literature, and in conversations with those close to him, he confessed to feeling a "physical emptiness" after the departure of his younger colleague. It is said that Chekhov's final words, spoken in German to his doctor, were: "Ich sterbe" ("I am dying"). He then drank a glass of champagne, lay on his side, and quietly passed away. When Tolstoy was told of these circumstances, he pensively remarked that it was entirely in Chekhov's spirit—to depart without grand words or gestures, with a glass of champagne.

Their first significant meeting occurred in 1895 when the 35-year-old Chekhov visited Yasnaya Polyana, where the 67-year-old Tolstoy received him with remarkable warmth. During this visit, an interesting and telling episode unfolded: Tolstoy was reading excerpts from his novel "Resurrection", and Chekhov, well-versed in the judicial system (partly due to his Sakhalin expedition), noticed an inaccuracy in the legal procedure, where the heroine was sentenced to an unreasonably short period of hard labour. Tolstoy not only took no offence at the observation from his "junior colleague" but also corrected the error in the final version of the novel.

They seemed to have nothing in common: on one side, a titled count, a "seasoned titan" of Russian literature, born during the reign of Nicholas I, descendant of an ancient noble lineage, owner of a luxurious estate; on the other, the son of a former serf, a modest doctor perpetually embarrassed by his own fame; one a prophetic moralist, the other an observer. Even the historical connection between their families bore a symbolically paradoxical character: Chekhov's grandfather was a serf belonging to the father of Chertkov—Tolstoy's closest friend and follower. One could say that in these two figures, two Russias converged: Tolstoy's patriarchal, aristocratic Russia, dying with "The Cherry Orchard", and Chekhov's new, non-aristocratic Russia. Despite their differences, judging by their letters, diaries, and observations of contemporaries, the writers respected one another, visited each other during illness, admired each other's genius, and also critiqued each other's creativity and life positions.

All the more remarkable, then, is their creative dialogue, transcending class, age, and ideological barriers—a dialogue whose form and content I wish to reconstruct in the text below. It consists of translations of diary entries, letters, memoirs, and other such authentic words by Tolstoy and Chekhov about each other. In most cases, these are not direct addresses but mentions in the third person, which I have intentionally translated into the second person, preserving 99% of the original speech and organising them according to some semblance of a non-chronological but logical-associative principle. Thus I hope to show how two radically different artistic approaches could still produce enduring masterpieces.

Tolstoy: You are Pushkin in prose. You never have superfluous details—each one is either necessary or beautiful.

Chekhov: If we speak of ranks, then in Russian art Tchaikovsky now occupies the second place after you, who have long been sitting in the first. I give the third to Repin, and take the ninety-eighth for myself.

Tolstoy: You are an incomparable artist of life... owing to your sincerity, you have created new, completely new forms of writing for the whole world. You write better than all Russian writers, even better than me.

Chekhov: And you, you! In our times, you are not merely a man, but a human colossus, Jupiter himself! Every night I wake up and read “War and Peace”. One reads with such curiosity and naïve wonder, as if one had never read it before. Remarkably good. Only I don't like those parts with Napoleon. Whenever Napoleon appears, there's immediately artifice and all sorts of tricks to prove he was more stupid than he actually was.

Tolstoy: You write life like a photographer—precisely, but without selection. I, on the other hand, am like an artist: from a thousand faces I create one in which the truth of the epoch is concentrated.

Chekhov: You forget that a photographer also makes a choice—where to point the lens. My camera shows what others consider unworthy of attention.

Tolstoy: But your pessimism destroys the soul. You are like a doctor who makes an accurate diagnosis but prescribes no medicine.

Chekhov: In my life I have never respected anyone as deeply, I might say unreservedly, as you. And I fear only you. Just think, it was you who wrote that Anna herself felt, saw, how her eyes sparkled in the darkness!

Tolstoy: I have read your “Grasshopper”. Written with such subtle humour!... This is a pleasure I am looking forward to, to reread all your works.

Chekhov: In one of your phrases there are three times "which" and twice "apparently." The phrase is made poorly, not with a brush, but as if with a sponge, but what a fountain gushes from under these "whiches," what flexible, harmonious, deep thought hides beneath them, what screaming truth!

Tolstoy: I read your story "On the Cart." Excellent in depiction, but rhetoric appears as soon as you want to give meaning to the story.

Chekhov: I’m going to write something strange.

Tolstoy: I went to see “Uncle Vanya” and was outraged. It is God knows what. In your plays questions aren't resolved, there is no content: only external technique is developed.

Chekhov: You know, I remember when I was at your place in Gaspra. You were still bedridden, but talked a lot about everything and about me, among other things. Finally, I rise to leave. You hold my hand, you say: “Kiss me”, and, having kissed me, you suddenly lean quickly to my ear and in such an energetic elderly rapid-fire manner: ”Nevertheless, I cannot stand your plays. Shakespeare wrote poorly, but you write even worse!”

Tolstoy: Because in them people only talk about their experiences, but do not act.

Chekhov: You are right—my heroes don't build barricades. But does all of life consist of barricades? Sometimes it's more important to show how a person imperceptibly destroys himself.

Tolstoy: Your “Seagull” is nonsense, worth nothing... “The Seagull” is very bad... The best thing in it is the writer's monologue, these are autobiographical traits, but in drama they are neither here nor there.

Chekhov: The boldness with which you discuss what you do not know and what, out of stubbornness, you do not want to understand. Thus, your judgements about syphilis, foundling homes, about women's aversion to copulation, etc., can not only be disputed, but directly expose a person who is ignorant. These shortcomings scatter like feathers in the wind; in view of the story's merit, you simply don't notice them.

Tolstoy: You are undoubtedly talented, but your plays are poor. If compared to Andreev's dramas, then perhaps they are good.

Chekhov: All great sages are despotic, like generals, and impolite and indelicate, like generals, because they are confident of impunity. Diogenes spat in beards, knowing that nothing would happen to him for it; you scold doctors as scoundrels and are rude about great questions, because you are the same Diogenes, whom one can't take to the police station or criticise in newspapers. So, to hell with the philosophy of the great men of this world! All of it, with all its sanctimonious afterwords, is not worth a single mare from “Kholstomer”.

Tolstoy: How good it is to read your stories! Sometimes, when it's touching or funny, I get emotional.

Chekhov: Your philosophy strongly moved me, it possessed me for about seven years... Now something in me protests. Prudence and justice tell me that there is more love for humanity in electricity and steam than in chastity and abstinence from meat.

Tolstoy: You take from life what you see, regardless of the content of what you see. But once you take something, you convey it amazingly vividly and clearly, down to the smallest detail... Whatever occupies you at the moment of creation, you recreate down to the last touches...

Chekhov: “Resurrection” is a remarkable novel. I especially like everything related to prisons and peasants, I like the chapter about the Englishman in Siberia... You will overshadow all of us for another fifty years.

Tolstoy: Art has become decrepit, entered a dead end, it is not what it should be. I have abandoned my novel "Resurrection" as I did not like it, and am writing only about art now.

Chekhov: To speak about art that way is the same as saying that the desire to eat and drink is outdated. Hunger is an old thing, in the desire to eat we have entered a dead end, but we still need to eat, regardless of what philosophers and irritable old men muse about.

Tolstoy: There is another great quality in you: you are one of those rare writers who, like Dickens and Pushkin and a few similar ones, can be read again and again, many times—I know this from my own experience... Your “Malefactor” is an excellent story. I have read it a hundred times.

Chekhov: I fear your death. If you were to die, a large empty place would form in my life. Firstly, I have never loved anyone as much as you; I am a non-believer, but of all beliefs I consider yours to be the closest and most suitable for me. Secondly, when you are present in literature, it is easy and pleasant to be a writer; even realising that one has done nothing and is doing nothing is not so frightening, since you accomplish enough for everyone.

Tolstoy: You are an incomparable artist... Truly incomparable... An artist of life... And the merit of your creative work is that it is comprehensible and akin not only to every Russian, but to every human being in general... And that is the main thing... You are sincere, and this is a great virtue; you write about what you saw and as you saw it... And thanks to your sincerity, you have created new, completely new forms of writing for the whole world that I have not encountered anywhere else. Your language is an unusual language.

Chekhov: You praise me, but with such an air as if I were your kitchen maid.

Tolstoy: We talked about immortality. I recognise immortality in the Kantian form; I believe that all of us (people and animals) will live in the beginning (reason, love), the essence and purpose of which is a mystery to us.

Chekhov: For me, this beginning appears in the form of a shapeless gelatinous mass; my individuality and consciousness will merge with this mass. Such immortality is not necessary for me, I do not understand it, and I was surprised that you did not understand why.

Tolstoy: I have reread “A Dreary Story”. You are right—one cannot live without a grand idea. But where to get it? You did not answer. Neither did I.

More on Chekhov:

More on Tolstoy:

Other literary relationships:

Plus, When Nietzsche Met Turgenev published on Apocrypha.

Very much enjoyed this!

Thank you so, so much, Vanya, for all these insights into and translations of Anton Chekhov -- of the related Russian writers, too, but especially Chekhov. He is my favorite writer, besides Scott Fitzgerald. Chekhov -- his thought and his writing -- is unmatched and probably will forever be. Please keep these coming. I know your research and translations represent a lot of work. Pardon my ignorance, but do you plan to put these translations into a book, or have you already?