What Dostoevsky and Turgenev promised each other

a literary correspondence between two great writers, 1864-1865

The relationships between great writers are always interesting to explore, for from them we don’t just learn more about their personalities but about the struggles they went through in their personal life, and, frankly, we just like gossip. I don’t enjoy reading biographies as much as I enjoy reading letters because they are written in an author’s voice and have personal quirks you wouldn’t encounter elsewhere. Although it’s easy to find letters online, it’s often hard to piece them together—you have to look for both sides of correspondence in separate places, often in different format, and tack the chronology and dates yourself. Sometimes it becomes a puzzle that reveals a real and quite ordinary human drama behind the extraordinary literary giants.

Read also my story about Turgenev meeting Nietzsche in the early 1870s.

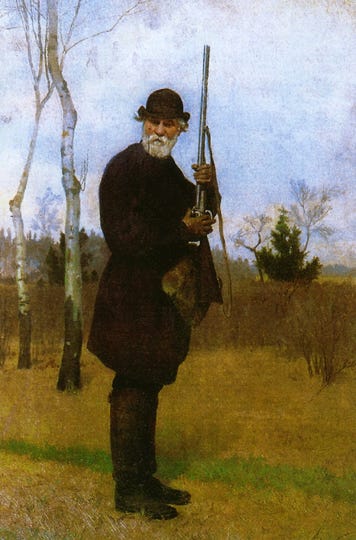

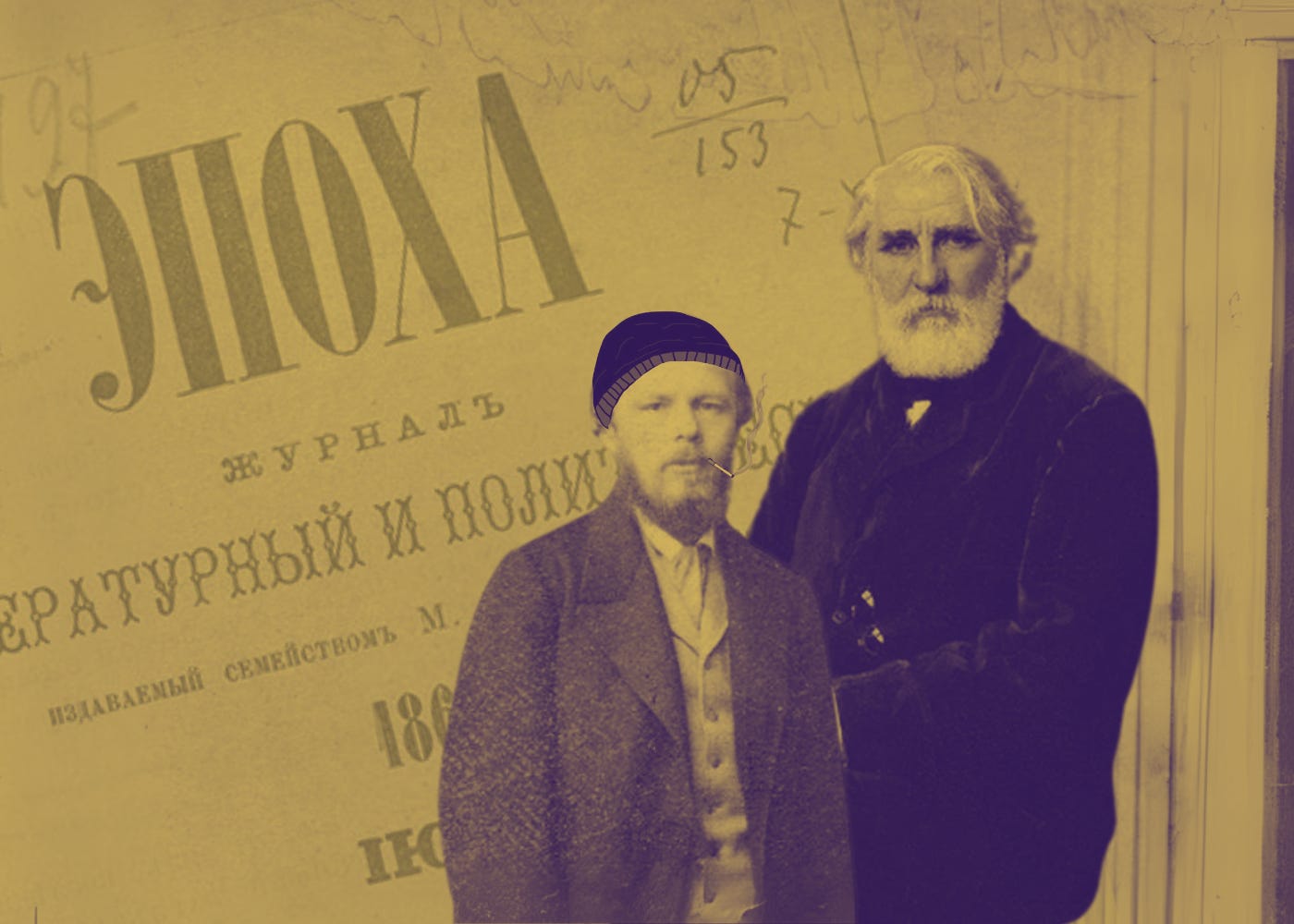

Fyodor Dostoevsky and Ivan Turgenev are certainly one of those. They lived and wrote in the same era, mid-late 19th century, a period that’s considered the most fruitful and important in the literary history of Europe. Both being great writers, their lives were drastically different: an aristocrat living comfortably in Europe and a broke gambler with “criminal experience”. In 1864-65, while Turgenev lived in Europe, met most famous European authors and thinkers, and, it must be said, promoted Russian literature among them, Dostoevsky lived in St. Petersburg and tried to run a literary journal called “Epokha” (Epoch), which I’ll write about separately later. After the death of his brother Mikhail in July 1864, Dostoevsky was left alone as the editor in chief of the mag and had to keep it afloat all by himself.

Though often positioned as ideological opponents—with Turgenev representing Western liberal values and Dostoevsky championing Slavophile traditionalism—their correspondence reveals a more nuanced relationship marked by mutual respect, if sometimes strained by differing literary sensibilities and personal circumstances. The exchange also revolves around Turgenev's story "A Dog," which becomes some sort of a cornerstone in their relationship and perhaps (only assuming) crucial for the survival of Dostoevsky’s journal.

Some of the letters have not been preserved so sometimes we have only one perspective available. Throughout the whole exchange, Turgenev was in Baden-Baden and Dostoevsky—in Petersburg. The correspondence begins in October 1864 with Turgenev responding to Dostoevsky's requests for contributions to Epokha. The news that Turgenev "has written and already completed a new work entitled 'The Dog'" and that this tale "will be printed [...] nowhere else but in the pages of 'Russky Vestnik'" was published in a few newspaper and journals. Asserting that not only "The Dog", but also Turgenev's next work was promised to "Russky Vestnik", they wrote: "What, then, is the meaning of the enticing announcements of 'Epokha', 'Biblioteka dlya Chteniya' and 'Severnoye Siyaniye', in which stories by I. S. Turgenev are definitely promised. Our well-known belletrist will need to write a great deal this year to satisfy all the hungry journalists!" These concluding words of the note apparently prompted Dostoevsky to write to Turgenev with a letter, in which he reminded Turgenev of the story he had promised for "Epokha". Below is Turgenev’s response:

My dear Fyodor Mikhailovich,

I have been intending to reply to your letter of 24th August1 - but then the hunting season began - and I forgot about it - for which I acknowledge my fault before you: your other letter of 20th September reminded me of my obligation, and I hasten to fulfil it. I shall begin with the assurance that my feelings towards your journal have not changed in the least - that I am ready with all my heart to contribute to its success, as far as I can - and I promise you that the first thing I write shall be placed with you2; but to specify the deadline, when this piece will be written, is impossible for me - because I have become completely lazy - and have not taken a pen in hand for more than a year. Whether I shall finally rouse myself - is known to God alone - but if this thing happens to me - my work is exclusively at your service. I have thought about you often during all this time, about all the blows that have struck you3 - and I sincerely rejoice that you have not allowed them to break you completely. I only fear for your health, that it might suffer from excessive labours. I myself am very and very sorry that I do not see "Epokha" here, I hope to arrange things better from next year.

Convey my friendly greetings to all your collaborators - and accept the assurance of my sincere interest in your activities and my attachment to you.

Yours faithfully,

I. Turgenev.

Just like Substack does now, Dostoevsky strived to attract big names to his platform, so by December 1864, he becomes more insistent. Having heard rumours that Turgenev had completed several stories, he writes directly asking for contributions, emphasizing how critical new material is for his struggling journal. On the 14th of December 1864, he writes:

Most esteemed Ivan Sergeyevich,

Forgive me for troubling you. You promised that, should you have a tale, you would not forget us. Now, for journals, it is the most critical time. If it were possible to publish even something of yours in January, it would be magnificent. I do not presume upon anything; moreover, you said not to trouble you. But here they are saying and have even printed that you have begun a series of stories and some are completed. Kovalevsky also spoke to me about this. If it is not disagreeable to you to publish even one of these stories now, then for God's sake, do so. If only this would not upset you in any way. We would, firstly, appear with you, and secondly, we would keep our word, and everyone would see that we have kept our word (in the journal announcement I only printed that I hope to publish in "Epokha" the first thing that you write).

Without boasting, I can say that our journal is becoming foremost, at least among those in Petersburg. We are in a great hurry, and this is very harmful to us, but the public is satisfied. We hear good reviews, even too good. But this is only the beginning. From next year (especially when we get back on schedule: the journal was delayed after my brother's death) things will be different, it will be three times better, I guarantee that. I sit day and night, I go about, I write, I proofread, I deal with printing houses and censors, etc. I cannot boast of good health, but at the end of April I shall definitely go abroad for 3 months to recuperate. I shall visit you as well. And from autumn I shall set to work again. Abroad I want to write a large novel. However, God knows what is still ahead, but for the time being I need to publish the journal better. And do you know what? It turns out that I am not entirely an impractical person. Affairs are going quite well. Subscriptions have begun late for everyone, but among Petersburg journals, it is heard, they have begun well only for us. I have never been in such hard labour as now. You can imagine how you would delight me with a satisfactory answer. But in any case, dash off at least two lines in response to this letter. Even two words, so that I would know. Support the journal, Ivan Sergeyevich!

Entirely yours, F. Dostoevsky.

December 14/64.

If you were to send a story even by the 1st of January, even then it would arrive in time. Even later than this would be possible.

But do not in any way consider my letter as importunity. I understood your words about not bothering you too well. In any case, do not be angry.

On the 28th of December 1864, Turgenev replies:

My dear Fyodor Mikhailovich,

I hasten to reply to your letter. In my desire to contribute, as far as I can, to the success of your journal - you do not doubt, I hope - but for now this remains only in the future. I give you my word of honour that I have absolutely nothing, not only finished, but even begun. - The story entitled "A Dog", which has been discussed in various journals, does indeed exist and is now in the hands of P. V. Annenkov; but I have decided, on the advice of all my friends, not to publish this trifle (of a few pages) - which, moreover, to speak frankly - has not turned out well for me. P. V. Annenkov will confirm this to you. The cause of the widespread rumour about a series of such stories - was a phrase I added to the title of "A Dog" - namely: "from the evenings at Mr F.'s". Annenkov himself will tell you - that for me to appear now before the public with such nonsense - would mean to finally kill all my credit. - I repeat, I can now only sympathise with you, be surprised at the boldness with which you, in our time, undertake literary work - and wish you health and strength - but nothing more. Believe me - this is not a phrase that an author says to an editor, - it is the very truth, which a sobered man communicates to a friend whom he respects.

I have arranged at the Berlin post office for "Epokha" to be sent to me; I myself plan to arrive in Petersburg during the month of March. I hope to find you cheerful and healthy - and until then, please accept the assurance of my sincere attachment and devotion.

I. Turgenev.

Later on 13th of February 1865:

Most esteemed Ivan Sergeyevich,

P. V. Annenkov informed me a week ago that I should send you my brother's debt for "Phantoms," three hundred roubles. I had no idea about this debt. Probably, my brother spoke to me about it at the time, but as my memory is very weak, I naturally forgot; besides, it did not directly concern me then4. And I am very sorry that I did not know about this debt last summer: I had a lot of money then, and I would certainly have sent it to you immediately, without your request.

I fear that now I am very late. But during these 8 days, the book (January issue) was being published, and additionally I was barely able to stand on my feet due to illness, and meanwhile, as I am almost alone in the administrative affairs of the journal, I was bustling day and night despite my illness. I also will not hide that there was little money; our subscription was delayed and has only now increased with the release of the 1st book.

In recent times, from 28 November, when our September issue was released, to 12 January (the release of the January issue)5, I, in 75 days, published 5 issues, each issue containing an average of 35 sheets. You can imagine what troubles this cost, and this alone will give you an idea of what I have now turned into? I do not know myself: I am some kind of machine.

Now I will have time not of 2 weeks, but already a month for the publication of the book. I hope to make the journal as interesting as possible. There are many debts: it will be very difficult, but I will endure the year, and by next year, we will stand firmly on our feet.

You wrote to me that you are surprised by my boldness in starting a journal in our time. Our time can be characterised by the words: that in it, especially in literature - there is no single opinion; all opinions are admitted, everything lives side by side; there is no common opinion, no common faith. For someone who has something to say and who (at least thinks) that he knows what to believe in, it would be a sin, in my opinion, not to speak. As for boldness - why not be bold, when everyone says whatever comes to mind, when the wildest opinion has the right of citizenship? However, what is there to talk about. Come here and take a closer look at our literature on the spot - you will see for yourself.

Lately, however, there have been several literary phenomena, several remarkable ones.

The day before yesterday, the 1st issue of "Sovremennik" was released with "The Voivode (Dream on the Volga)" by Ostrovsky. I do not know what it is; I have not read it yet, I was sitting over the proofs; some say that this is the best that Ostrovsky has written, others do not know what to say.

I am sending you with this, through Ginzburg's office, a transfer of 300 roubles.

Annenkov said that you will not come to us soon. Is that true?6

By the way: I wonder why you consider that your story "A Dog" (which I have not read) is so insignificant that to publish it now means to harm yourself in literature. This is strange to me, Ivan Sergeyevich! Can you really harm yourself, even with an insignificant story?7 So what if your small story appears before a large poem? Who has not written small stories?

Farewell. Your most devoted

Fyodor Dostoevsky

On the 21 February 1865, Turgenev replies:

My dear Fyodor Mikhailovich,

I hasten to inform you that I have received your bill of exchange for 300 roubles and thank you. I would certainly not have troubled you if my daughter's wedding with all its foreseen and unforeseen expenses had not forced me to knock on all doors. I hope that this payment has not inconvenienced you too much.

What you say about your activities simply frightens me, a lazy Baden burgher as I have become. I am very sorry that your health is unsatisfactory: take care not to overwork yourself! Better take a young and active assistant for the administrative part. This expense will be repaid with interest.

I am not hesitant to publish "A Dog" because this work is small - but because, by the general verdict of my friends, it has failed. Better to remain silent than to speak poorly.

From Annenkov's letters - I notice that recently literature seems to have revived: he tells me about Tolstoy's novel, about Ostrovsky's drama8. I would like to read all this - but, it seems, I will have to postpone it until my return, which will be no later than 15-20 April. Then I will also become acquainted with your journal.

I wish you all the best, starting with health - and I warmly shake your hand.

Yours faithfully,

Iv. Turgenev.

He won’t, however, become acquainted with the journal because “Epokha” had ceased publication with its February 1865 issue due to financial difficulties. Perhaps because of those 300 rubles, perhaps because “A Dog” didn’t go to print, perhaps for other reasons…

Following that, the correspondence continues in August 1865. Dostoevsky, now travelling in Europe ostensibly for his health, finds himself in dire financial straits in Wiesbaden, Germany after gambling away what little money he had brought with him. On the 3rd of August he writes to Turgenev:

Most kind and esteemed Ivan Sergeyevich, when I met you about a month ago in Petersburg, I was selling my works for whatever was offered, because I was being put in debtors' prison for the journal debts which I had the stupidity to transfer to myself. Stellovsky bought my works (the right to publish in two columns) for three thousand, part of which in promissory notes. From these three thousand I somehow momentarily satisfied some creditors and gave out the rest to those whom I was obliged to pay, and then went abroad to improve my health at least a little and to write something. Of all the three thousand I left myself for abroad only 175 silver roubles, and could not spare more.

However, two years ago in Wiesbaden I won in one hour up to 12,000 francs.9 Although I was not now thinking of improving my circumstances through gambling, I did indeed want to win about 1,000 francs, just to live through these three months. I have been in Wiesbaden for five days already and have lost everything, everything down to the last penny, and my watch too, and I even owe the hotel.

I find it both disgusting and embarrassing to trouble you with myself. But, besides you, at this moment I positively have no one to whom I could turn, and secondly, you are much more intelligent than others, and consequently, it is morally easier for me to turn to you. Here is the matter: I address you as a man to a man and ask you for 100 (one hundred) thalers. Then I am expecting some money from Russia from one journal ("Library for Reading"), from where they promised me, upon my departure, to send a tiny bit of money, and also from one gentleman who should help me.10 It goes without saying that I may not be able to return it to you earlier than three weeks. However, perhaps I will return it earlier. In any case, I sit here alone. My soul feels wretched (I thought it would feel worse), but mainly, I am ashamed to trouble you; yet when one is drowning, what can one do.

My address is: Wiesbaden, Hotel "Victoria", a M-r Theodore Dostoiewsky.

What if you are not in Baden-Baden?

Entirely yours, F. Dostoevsky.

A few days later, Dostoevsky writes again:

I thank you, most kind Ivan Sergeyevich, for your sending of 50 thalers. Though they have not helped me radically, they have nevertheless helped me very much. I hope to return them to you soon. I thank you for your wishes, but they are somewhat difficult for me to fulfil. Moreover, I have caught a cold, probably while still in the carriage, and since Berlin I have been feeling feverish every day. In any case, I hope to see you very soon. And meanwhile, I sincerely shake your hand and remain

Entirely yours,

F. Dostoevsky.

However, as both of these guys tend to, M-r Theodore Dostoiewsky forgot about this debt and only returned it in 1876, a full eleven years later.

This marks an end to this little, yet perhaps more significant than it seems, story within Russian literary history. For Dostoevsky, we see his remarkable resilience in the face of compounding personal tragedies and financial disasters, but also glimpse the gambling addiction that would inspire his novel “The Gambler” published in 1866. For Turgenev, we observe his exacting literary standards and his reluctance to publish work he considered inferior, as well as his somewhat detached but not unsympathetic attitude toward Dostoevsky's struggles. Despite their philosophical and aesthetic differences, which would occasionally flare into public disagreement in later years, this correspondence demonstrates a fundamental professional respect between two masters of Russian literature at very different points in their careers and personal circumstances.

"A Dog," that story Dostoevsky was begging Turgenev to publish in “Epokha”, would remain unpublished until 1882, when it appeared as part of his collection "Poems in Prose" in the journal “Vestnik Evropy”11 and didn’t destroy Turgenev’s reputation. Either he substantially revised it since 1864 when he deemed it unworthy or just decided “fuck it”, we can only read the final version of it:

A Dog

a poem in prose

There are two of us in the room: my dog and I. Outside, a terrible, furious storm is howling.

The dog sits before me - and looks straight into my eyes.

And I, too, look into its eyes.

It seems as if it wants to tell me something. It is mute, it has no words, it does not understand itself - but I understand it.

I understand that at this moment both it and I are experiencing the same feeling, that there is no difference between us. We are identical; in each of us burns and glows the same tremulous flame.

Death will swoop down, will wave over it with its cold, broad wing...

And the end!

Who will then discern what kind of flame exactly burned in each of us?

No! it is not an animal and a human exchanging glances...

It is two pairs of identical eyes fixed upon each other.

And in each of these pairs, in the animal and in the human - the same life huddles timidly against another.

This letter from Dostoevsky is unknown. It apparently was similar in content to Dostoevsky's letter to Ostrovsky of the same date and contained a request to support "Epokha" with his participation.

This promise was not fulfilled by Turgenev.

Turgenev is referring to the prohibition of the Dostoevsky brothers' journal "Vremya" (24 May 1863), the death of the writer's first wife Maria (15 April 1864), and the death of his brother Mikhail (10 July 1864).

They, apparently, both forget a lot of things.

The January issue of "Epokha" (Epoch) for 1865 came out not on 12 January, but on 13 February.

P. V. Annenkov's information turned out to be inaccurate. For a short time, Turgenev came to Russia in the summer of the same year 1865. In the first days of July 1865, he met with Dostoevsky.

The majority of reviews about the story "The Dog" were indeed negative according to historical sources.

Turgenev is referring to a letter to him from P. V. Annenkov dated February 18, 1865. It could have been received by Turgenev on the very day of writing the letter to Dostoevsky.

Dostoevsky is referring to his trip to Wiesbaden in 1863.

He is referring to Herzen.

Vestnik Evropy (Herald of Europe) was a prominent liberal monthly journal published in St. Petersburg from 1866 to 1918.

Recently wrote an article you might enjoy, no pressure of course: https://dbtaylor.substack.com/p/a-reason-to-read-crime-and-punishment?r=22o631

“I have become completely lazy” why find excuses when you can simply tell the truth?