The Art of Chekhovian Eurotrip

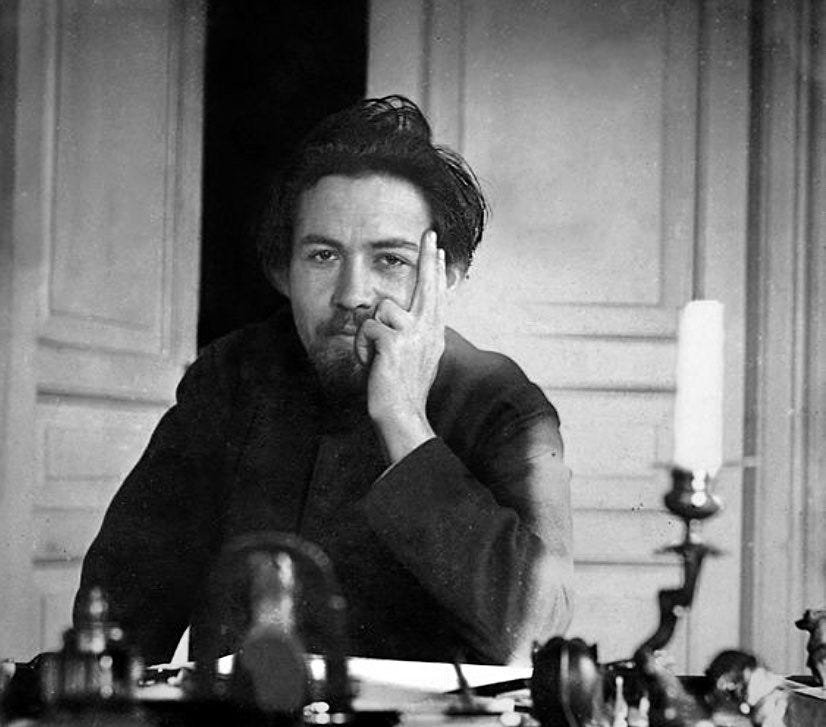

selected Anton Chekhov's letters from Europe, 1891

If Chekhov had a social media account, he would've been by far the best in the world at platitudes, aphorisms, etm. and would surely get thousands of likes under each post. I noticed that somehow in the English-speaking circles he's known more for short stories, while for me, even though I love the stories, too, his more important and influential works are undoubtedly plays and his letters. In the letters, you can see his real character, or the one he seemed to prefer to play—not just a serious doctor with a professorial look who "surgically dissected human condition" (ew, can't be more cliche than that) but also a jester, witty and playful. Today I want us to look more into that side of his by joining him on his first Eurotrip and imagining he wrote a travel blog instead of letters.

In the spring of 1891, Chekhov visited Austria, Italy, France, and Germany for the first time. This trip was a breath of fresh air after intense work and the distressing impressions from his previous journey— Sakhalin Island1, which is also well-documented and worth looking into if you’re a fan of either Chekhov or that part of the world or both (maybe later I’ll share that too). During his Eurotrip, as always, Chekhov maintained an active correspondence sharing his impressions of what he had seen and experienced. It is a genuine literary account and a portrait of Europe through the eyes of a Russian writer, filled with lively observations, astute characterisations, and, most importantly, inimitable humour. So, let’s see the 1891 Europe through his own eyes words.

Departure from Russia

It begun on 11 March 1891,2 together with his publisher and friend Alexei Suvorin, Chekhov headed off to through Vienna towards the Adriatic coast. Suvorin was an influential publisher of the newspaper "Novoye Vremya" (New Times) and was significantly older and wealthier than Chekhov (who was 31 at the time), often acted as his mentor and patron, especially for this, supposedly expensive trip.

Vienna, Austria

On 13 March 1891, they arrived in Vienna. Even though the city was a cultural centre of Europe, Chekhov seemed to perceive this city merely as an intermediate stop on the way to a more enticing destination—Italy.

"A pleasant city, but my soul awaits Venice... and freedom from suitcases."

Trieste and Verona, Italy

After Vienna, Chekhov visited Trieste and Verona.

"Trieste—a port and wind."

"Verona—misty, but with Juliet's balcony."

Venice, Italy

On 24 March 1891, Chekhov arrived in Venice, which made the strongest impression on him throughout the entire journey. He expressed his delight in numerous letters:

"I have never seen a more remarkable city than Venice in my life. It is pure enchantment, brilliance, the joy of life."

"Instead of streets and lanes—canals, instead of cabbies—gondolas, and the architecture here is amazing."

"The best time in Venice is the evening. In the evening, being unaccustomed to it, one could die [from rapture]."

"Listening to the organ in a Catholic cathedral makes one want to embrace Catholicism."

"Gondolas, St. Mark's Square, water, stars, Italian women, evening serenades... in a word, all is lost!"

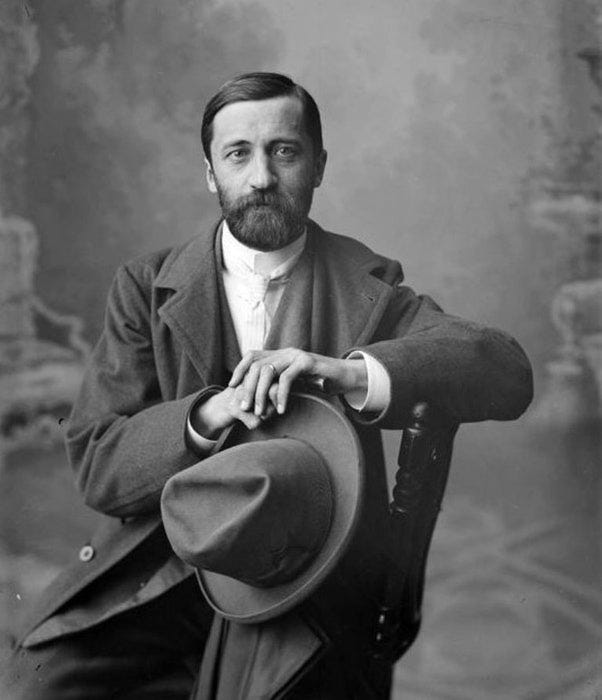

By that ironic hyperbole Chekhov, of course, meant his utter captivation with the city. There he met two major figures of Russian Symbolism, Dmitry Merezhkovsky and his wife Zinaida Gippius3 who shared his feelings:

"Merezhkovsky, whom I met here, has gone mad with delight. For a Russian, poor and downtrodden, here in this world of beauty, wealth, and freedom, it is not difficult to lose one's mind."

Bidding farewell to Venice, Anton Pavlovich wrote a phrase that became one of the most famous from his travel notes:

"Only a fool would not visit Venice."

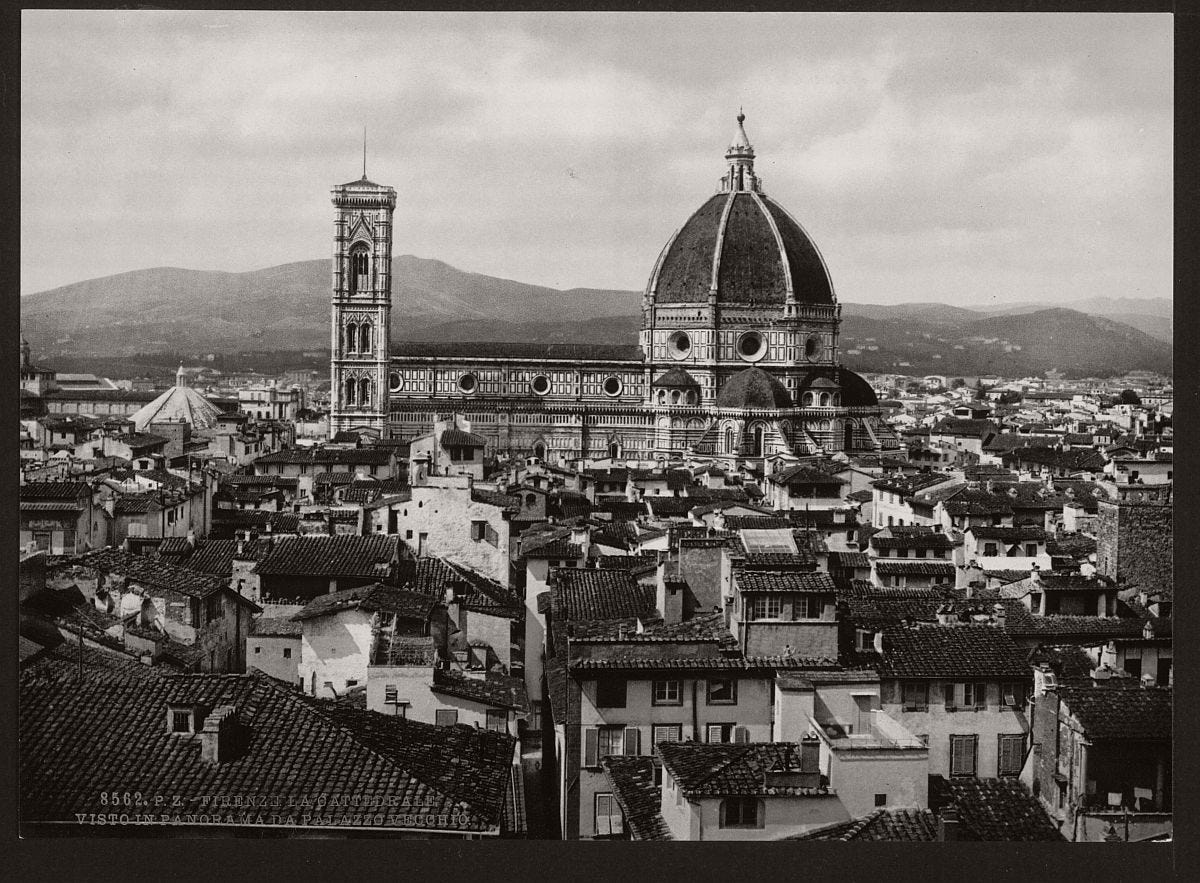

Florence, Italy

Chekhov spent 29-30 March in Florence, a city known for its artistic treasures and Renaissance architecture. However, his impressions were marred by bad weather and fatigue from endless excursions:

"I am in Florence. Cold. Khondria."4

"At every step—a picture shop, but in my soul, there is toska."5

So, the guy didn’t enjoy Florence, imagine that!

Merezhkovsky also remarked that he saw no enthusiasm in Chekhov when they met. And according to Suvorin, Chekhov was more attracted to everyday trifles and showed little interest in art. Chekhov himself partially gave reason to think this way about his perception of the journey when he wrote that "Rome resembles Kharkiv, and Naples is dirty6," or that "foreign train carriages and railway regulations are worse than ours. Our carriages are more comfortable, and people are more good-natured. Here at the stations there are no buffets."

Rome, Italy

Chekhov was in Rome from 1 to 3 April. His impressions here were ambivalent:

"I visited St. Peter's Basilica, saw the Vatican, the Colosseum, the Capitol... All of this oppressed me with its grandeur."

"Alas, I am with Suvorin... In Venice, we lived in the best hotel, like doges; here in Rome, we live like cardinals."

Yet Rome did not evoke the same admiration in Chekhov as Venice had:

"Rome gave me the impression of a provincial town."

The weather was not pleasant either:

"In Rome, the weather is a hindrance; it's raining. In an autumn coat, it's hot, and in a summer coat, it's cold."

And the guy was tired (again):

"My back aches and the soles of my feet burn from walking. Horror, how much we walk!"

In a letter to Maria Kiseleva, a friend and an owner of an estate his family spent summers at, Chekhov summarises his impression of Rome and Italy so far:

The Pope of Rome has instructed me to congratulate you on your name day and to wish you as much money as he has rooms. And he has eleven thousand rooms! Wandering around the Vatican, I withered from exhaustion, and when I returned home, it seemed to me that my legs were made of cotton wool.

I dine at the table d'hôte. Can you imagine, sitting opposite me are two Dutch girls: one resembles Pushkin's Tatyana, and the other her sister Olga. I look at both throughout the entire dinner and imagine a neat little white house with a turret, excellent butter, superior Dutch cheese, Dutch herrings, a respectable pastor, a dignified teacher... and I want to marry the Dutch girl, and I want to be painted together with her on a tray near a neat little house.

I have seen everything and climbed wherever I was told to. Was given things to smell - I smelled. But so far I feel only fatigue and a desire to eat shchi7 with buckwheat porridge. Venice enchanted me and drove me mad, but when I left it, Baedeker8 and bad weather set in.

Goodbye, Maria Vladimirovna, may the Lord God preserve you. Lowest bow from me and from the Pope of Rome to His High-born, Vasilisa and Elizaveta Alexandrovna.

Neckties are amazingly cheap here. Terribly cheap, so that I might even start eating them. One franc per pair.

Tomorrow I'm going to Naples. Wish that I meet there a beautiful Russian lady, preferably a widow or a divorced wife. The guidebooks say that when traveling through Italy, a romance is an essential condition. Well, devil take it, I agree to everything. If it's to be a romance, then a romance it shall be.

Do not forget the sinful one, sincerely devoted to you and respecting you, A. Chekhov.

Regards to the starlings.

Naples and Surroundings, Italy

Chekhov spent 4-7 April in Naples and its surroundings:

"We can see everything: the sea, Vesuvius, Capri, Sorrento... Magnificent, though expensive."

"In Naples, there is a magnificent arcade... You, Masha9, and you, Lika10 would go mad with delight."

"I was at a barbershop and saw how they cut one young man's beard... They cut remarkably... Probably a bridegroom or a cardsharp."

The salon's interior amazed the writer with its luxury—the ceiling and all the walls were entirely mirrored. Chekhov joked that he felt not in a barbershop but as if in the Vatican with its 11 000 rooms.

"What torture it is to climb Vesuvius! You take a step forward—and half a step back, your soles hurt, your chest feels heavy... You walk and walk, and the summit is still far away."

"The crater of Vesuvius is several fathoms in diameter. I stood on its edge and looked down, as into a cup."

"It is very frightening, and at the same time, one wants to jump down. I now believe in hell."

"I am terribly tired. In certain parts of my mortal body, there is a feeling as if I had been flogged in the gendarmerie."

Chekhov also visited the ancient city of Pompeii:

"I walked along the streets of this city and saw houses, temples, theatres, squares... I saw and marvelled at the Romans' ability to combine simplicity with comfort and beauty."

Nice, France

After completing the Italian part of his journey, Chekhov headed to France. From 8 to 17 April, he was on the Côte d'Azur:

"The weather is beautiful, I am resting. There are many Russians in Nice. Sea and tranquillity."

Chekhov's stay in Nice also included more adventurous episodes. In a particularly revealing letter from Monday of Holy Week, he describes an excursion to nearby Monaco and his first—and last—experience with gambling:

We are living in Nice, on the seashore. The sun is shining, it's warm, green, fragrant, but windy. At a distance of one hour's ride from Nice is the famous Monaco; there is a place Monte Carlo, where they play roulette. Imagine the halls of the Noble Assembly, beautiful, high and wider. In the halls are large tables, on the tables roulette, which I will describe to you when I arrive. The day before yesterday I went there and lost. The game is terribly captivating. After losing, I and Suvorin began to think, thought, and devised a system of play with which you will definitely win. Yesterday we went, taking 500 francs each; from the very first bet I won a couple of gold pieces, then more and more, my waistcoat pockets sagged from gold; I had in my hands French coins even from 1808, Belgian, Italian, Greek, Austrian... Never at any other time have I seen so much gold and silver. I started playing at 5 o'clock, and by 10 o'clock I didn't have a single franc in my pocket, and I was left with only one thing: pleasure from the thought that I had bought myself a return ticket to Nice. That's how it is, my dears! You, of course, will say: "What vileness! We are struggling, and he is playing roulette there." Quite right, and I permit you to slaughter me. But I personally am very pleased with myself. At least now I can tell my grandchildren that I played roulette and am familiar with the feeling that is excited by this game.

Near the casino with roulette there is another roulette - the restaurants. They fleece you terribly here and feed you magnificently. Each portion is a whole composition, before which one must kneel in reverence, but by no means dare to eat it. Every morsel is abundantly garnished with artichokes, truffles, all kinds of nightingale tongues... And, my God in heaven, to what degree this life with its artichokes, palms, scent of bitter oranges is despicable and nasty! I love luxury and wealth, but the local roulette luxury makes on me the impression of a luxurious water closet. There is something hanging in the air that, you feel, insults your decency, vulgarizes nature, the noise of the sea, the moon.

…

Are you keeping the newspapers?

Greetings to everyone: Alexey with his aunt, Semasha, the handsome Levitan, golden-haired Likisha, the old woman, and everyone in general. Well, stay healthy. May the heavens preserve you.

I have the honor to report and remain bored,

Antonio.

Paris, France

On 17-18 April, Chekhov arrived in Paris.

"Everything has changed under our zodiac. Instead of going to Milan, as I wrote, we went to the hearth of civilisation - Paris. We left Nice at noon and arrived in Paris at 8 o'clock in the morning. The train was racing like mad. While riding from the station, I saw the Eiffel Tower in the fog, and now I am sitting in my room, washing myself and putting my mug in order."

"Paris is the hearth of civilisation. But it is so noisy. Where to escape from breakfasts!"

Chekhov went to an exhibition, visited the Chamber of Deputies during a tumultuous session regarding the disorders in Fourmi, and became acquainted with Parisian entertainments:

"Men girding themselves with boas, ladies lifting their legs to the ceiling, flying people, lions, café-chantants,11 dinners and breakfasts are beginning to disgust me. It's time to go home. I want to work."

Too much food, he thought:

"I am terribly tired of breakfasting, dining, and sleeping. Abroad, too much time is spent on all this. Siberia, where travellers neither breakfast, nor dine, nor sleep, is much better in this respect. There you don't eat and therefore feel as if on wings."

But:

"In Paris, I saw naked women."

In Paris, he also celebrated Easter12 in the embassy church and managed to visit an art exhibition:

"I was at the art exhibition (Salon) and couldn't see half of it due to my short-sightedness. By the way, Russian artists are much more serious than the French. In comparison with the local landscape painters I saw yesterday, Levitan is king."

In a letter dated 21 April, he describes the Easter celebrations and the busy Parisian streets:

"Today is Easter. So, Christ is risen! This is the first Easter I am spending away from home. I arrived in Paris on Friday morning and immediately went to the exhibition. Yes, the Eiffel Tower is very, very high. I saw the other exhibition buildings only from the outside, as inside there was cavalry, prepared in case of disorders. On Friday, disturbances were expected. People walked in crowds through the streets, shouted, whistled, were agitated, and the police dispersed them. To disperse a large crowd, ten policemen are enough here. The police make a concerted push, and the crowd runs like mad. I was honoured to be caught in one of these pushes: a policeman grabbed me by the shoulder blade and began to push me forward."

"There is a mass of movement. The streets swarm and boil. Every street is like a turbulent Terek. Noise, hubbub. The pavements are occupied by tables, and at the tables - Frenchmen, who feel at home on the street. Excellent people. However, you cannot describe Paris, I will postpone its description until my arrival."

Germany

"German cities are like medicine cabinets: clean, but dull."

Final impressions

So, did Chekhov enjoyed his trip? Given both Suvorin and Merezhkovsky thought Chekhov didn’t really enjoy Europe, it only adds more interests to look at his letters directly. It seems his demeanour and behaviour is drastically different to his internal perception and how he describes it upon further reflection. Yet Chekhov was also surprised he gave away the impression that he didn’t like his Eurotrip. In his response to Suvorin after their return he wrote:

"...I would like to know who is trying so hard, who has informed the entire universe that I supposedly did not like being abroad? Lord God Almighty, I have not mentioned this to anyone with a single word... What should I have done? Howl with delight? Break windows? Hug the French?"

In 1890, Chekhov undertook an arduous journey to Sakhalin Island, where he studied the living conditions of convicts and exiles. This journey lasted several months and required enormous physical and emotional strain from the writer. The result of the trip was the book "Sakhalin Island", published in 1893-1894.

All dates in the article are given according to the Julian calendar (Old Style), which was used in Russia until 1918 and lagged 12 days behind the Gregorian calendar adopted in Europe. Thus, 11 March in the Old Style corresponded to 23 March in the New Style. Not that it’s too important but FYI.

Dmitry Merezhkovsky (1865-1941) was a Russian writer, poet, critic, translator, and one of the founders of Russian Symbolism. His wife, Zinaida Gippius (1869-1945), was also a famous poet, writer, and critic. Together, they formed one of the most influential literary couples in Russia of their time.

"Khondria" is my Anglicisation of the Russian word "хандра" (khandra), a culturally specific word to describe melancholy or spleen. I decided to keep it because of the unique connotation it carries, combining elements of ennui, world-weariness, and a specific form of existential gloom.

"Toska" (тоска) is a uniquely Russian concept that Vladimir Nabokov famously described as untranslatable. In his notes to his translation of "Eugene Onegin," Nabokov wrote: "No single word in English renders all the shades of toska. At its deepest and most painful, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning. In particular cases it may be the desire for somebody or something specific, nostalgia, lovesickness." Similar concepts exist in other languages, such as the Portuguese "saudade" or the Welsh "hiraeth," but none captures the exact Russian sensibility of "toska".

It still is.

"Shchi" (щи) is a traditional Russian fermented cabbage soup. A staple on Russian tables since at least the 9th century, shchi was consumed by everyone from peasants to tsars. The famous Russian proverb declares, "Щи да каша — пища наша" ("Shchi and porridge are our food"). Longing Russian food is typical homesickness, even for Chekhov.

"Baedeker" refers to a series of popular guidebooks published since the 1830s by German publisher Karl Baedeker and his successors. By the end of the 19th century, these guidebooks, distinguished by their accuracy of information and practical advice, had become an essential attribute for travellers in Europe. The name "Baedeker" became synonymous with any guidebook.

"Masha" is Maria (Mariya) Pavlovna Chekhova, Anton Chekhov's younger sister. She was one of his closest family members and frequent correspondents. Many of his European travel letters were addressed to her or to his family with specific messages for her. Later in life, after Anton's death, Masha became the dedicated keeper of her brother's legacy, establishing the Chekhov House Museum in Yalta.

Lydia (Lika) Mizinova (1870-1937) was a close friend of Chekhov, with whom the writer was once in love. Their relationship did not work out, but they maintained friendship and correspondence. Lika became the prototype for Nina Zarechnaya in Chekhov's play "The Seagull".

Café-chantant (French for "singing café") was a popular establishment in the late 19th century where visitors could not only drink and eat but also watch an entertainment programme with songs, dances, and various acts. It was a precursor to modern cabaret.

In 1891, Orthodox Easter fell on 21 April according to the Old Style (3 May according to the New Style). In his letter home dated 21 April, Chekhov notes: "Today is Easter. So, Christ is risen! This is the first Easter I am spending away from home."

Most excellent piece. Thank you!

Fantastic piece and very insightful footnotes! I've never seen anyone on Substack so rooted into intricacies of translation and word use.

Браво! Жду больше постов о русских писателях!