Chekhov's Romantic Escapades

"Chekhov or Checking out?"

Author’s note:

This piece today is another biographical note on Anton Chekhov to continue the series I started last week with this post. It isn’t a part II, for there’s no order to it, in fact, chronologically, we’re going backwards, but I’d still recommend to check out the previous post whenever you feel like it!

If I were to pick a single phrase, Chekhov’s own words, from that piece to build a natural link between that and this, it’d be “In Paris, I saw naked woman.” Apparently, it wasn’t the first time Chekhov saw naked women. A year prior to his Eurotip he went to Siberia, to Sakhalin (on that later) and then to Ceylon, where he also saw quite a bit.

Please enjoy “Chekhov without the pince-nez”!

Beams of appreciation,

Ivan | Vanya | Vanechka1

The blessed image of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov—an elegant intellectual with pince-nez and walking stick—creates the impression of a reserved, almost chaste doctor and humanist. However, Chekhov himself, a 182-centimetre-tall gigachad2 with a deep bass voice, would have only scoffed resentfully at this "sanitised" picture. The most famous portrait of Chekhov presents him exactly this way. Osip Braz wanted to create a serious image of the classic author, but the result was a generalised image of a Russian intellectual of the late nineteenth century. Chekhov himself later noted, "If I've become a pessimist and write gloomy stories, my portrait should be blamed."

Let's forget this image and use “Chekhov without the pince-nez” henceforth:

He was one who valued carnal pleasures no less than literary triumphs. With his determination and charm, Chekhov conquered women, and close friends knew him certainly not as a puritan. His personal correspondence, letters, diaries, and memoirs of contemporaries are a curious source of rather piquant details and jokes that Soviet publishers long suppressed so as not to tarnish the image of a literary classic. Censors cut from Chekhov's letters all mentions of sexual escapades and even episodes of impotence. Anton Pavlovich himself, one must assume, would have laughed at the commotion caused by these "sensational" revelations about his intimate life.

They say that young Anton Pavlovich gained his first experience in intimate matters at a brothel at the age of thirteen. Yes, it seems, in 19th century Imperial Russia, a teenager visiting a public house wasn't something extraordinary but mundane, like going to a bathhouse, as biographers note. This detail is usually omitted in school biographies in favour of the "PG-13" version. But the fact remains: from the age of thirteen, Chekhov knew what he wanted from life and continued to visit brothels throughout most of his youth.

While studying medicine in Moscow and taking his first steps in literature, Chekhov remained a bachelor and had no desire to tie himself down with serious relationships, preferring to visit "houses of tolerance."3 Chekhov called this "the commercial variant of love." According to recollections, Chekhov never missed a brothel on his path. He approached this with a researcher's enthusiasm—both as a doctor and as a writer. Later, having already become famous, Anton Pavlovich admitted that he preferred to keep "women (with the exception of prostitutes)" at "letter's distance," not letting them get too close so that love wouldn't interfere with his work.

His brother Alexander Pavlovich Chekhov, himself a writer and wit, came up with an ideal answer the question "how are you?", summarised his (and incidentally his brother's) life philosophy:

I don't live splendidly,

But I don't curse my fate:

I may not fuck impressively,

But I fuck nonetheless

Such bold frankness wouldn't shock Chekhov at all. On the contrary, he himself wasn't above boasting of his successes in the romantic field amongst his close circle of friends. In letters to his publisher and older comrade and patron Alexei Suvorin (who took him on a trip to Europe), Anton Pavlovich often reflected on relations between the sexes:

Women who are used, or, to put it in Moscow terms, are cockroached on every sofa, are not wild – they are dead cats suffering from nymphomania. A sofa is a very inconvenient piece of furniture. It is accused of fornication more often than it deserves. I have only used a sofa once in my life and cursed it.

Behind the apparent cynicism there was, perhaps, some disappointment in women. For a long time, Chekhov avoided serious romances, and intimacy without love was for him a safe harbour, free from the threats of jealousy or emotional dramas.

The girls with whom Chekhov attempted to start romances, often simultaneously, were jokingly called "antonovki" ("Anton's little apples"), referring to his name and a well-known variety of apples. Biographers have counted more than thirty names of women with whom Chekhov had close relationships. Among them were singers and artists, literary figures, ballerinas, actresses, and others. Chekhov paid attention to each one, charmed them, flirted, but as soon as things went too far, he evasively backed away. He jokingly called himself a fugitive: "I would fall in love, conquer, and then flee in horror, fearing responsibility."

In 1890, Chekhov made his famous journey to Sakhalin (more on that another time) with the humanitarian mission of studying the lives of convicts. But, as he himself jokingly admitted, what "carried him to the Far East" was not only noble curiosity but also a sort of adventurism, "a desire to descend into hell".

In one of his letters from that period, Anton Pavlovich wrote with sly melancholy that if it weren't for the Sakhalin venture, he would have spent that summer so merrily that "it would have made the devils sick with envy." Supposedly, "as if on purpose, every day there were new acquaintances, more and more maidens, and such that if one were to gather them at one's dacha, there would be a most merry and consequential kavardak4."

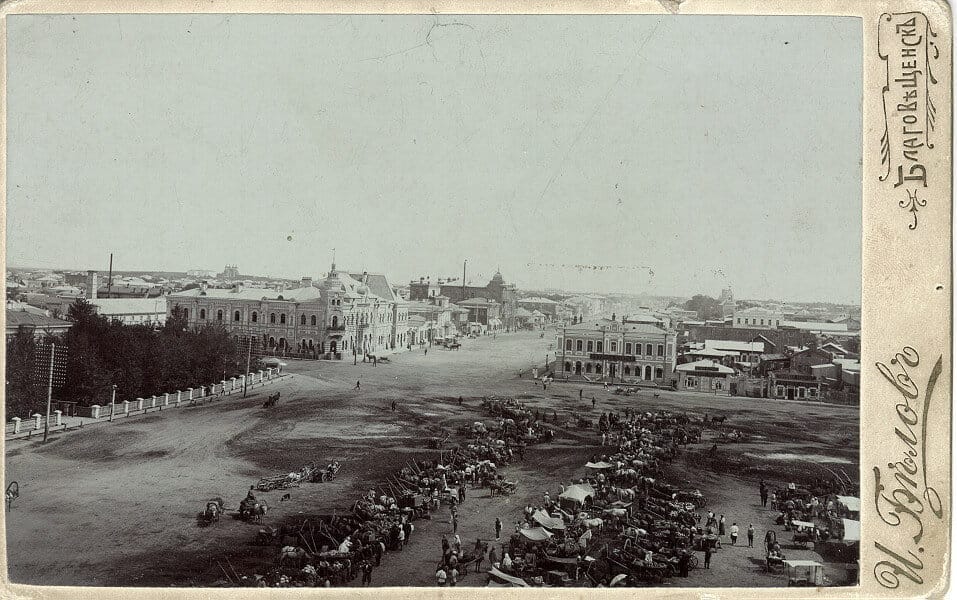

Arriving in June 1890 in the city of Blagoveshchensk on the Amur River, he found himself on the border with China and became acquainted with the world of Eastern brothels.

In a letter dated 27 June 1890 to the same Suvorin, Anton Pavlovich described with enthusiasm and medical meticulousness his experience with a Japanese geisha. This unique document is perhaps one of the most candid in the history of Russian literature. Here is a fragment from it:

From Blagoveshchensk onwards, one encounters Japanese, or, more precisely, Japanese women. These are small brunettes with large intricate hairstyles, with beautiful torsos and, as it seemed to me, with short hips... When out of curiosity one employs a Japanese woman, one begins to understand Skalkovsky5, who, they say, had himself photographed with some Japanese whore. A Japanese woman's little room is clean, Asian-sentimental, filled with small trinkets: no basins, no rubber goods, no generals' portraits. The bed is wide, with one small pillow. You lie on the pillow, and the Japanese woman, in order not to ruin her hairstyle, places a wooden stand under her head... A Japanese woman understands modesty in her own way: she doesn't extinguish the light and when asked what this or that is called in Japanese, she answers directly and, poorly understanding Russian, points with her fingers and even takes things in her hand – all this without putting on airs or being coy, like Russian women. And all this time she laughs and sprinkles the sound "tts". In the act, she displays astonishing mastery, so that it seems to you that you are not simply having relations, but participating in high-school equestrian sports. Upon finishing, the Japanese woman pulls from her sleeve with her teeth a sheet of cotton paper, catches you by the "little gentleman" and unexpectedly for you performs a wiping, whereupon the paper tickles your stomach. And all this coquettishly, laughing...

The amount of detail is astonishing, indeed.

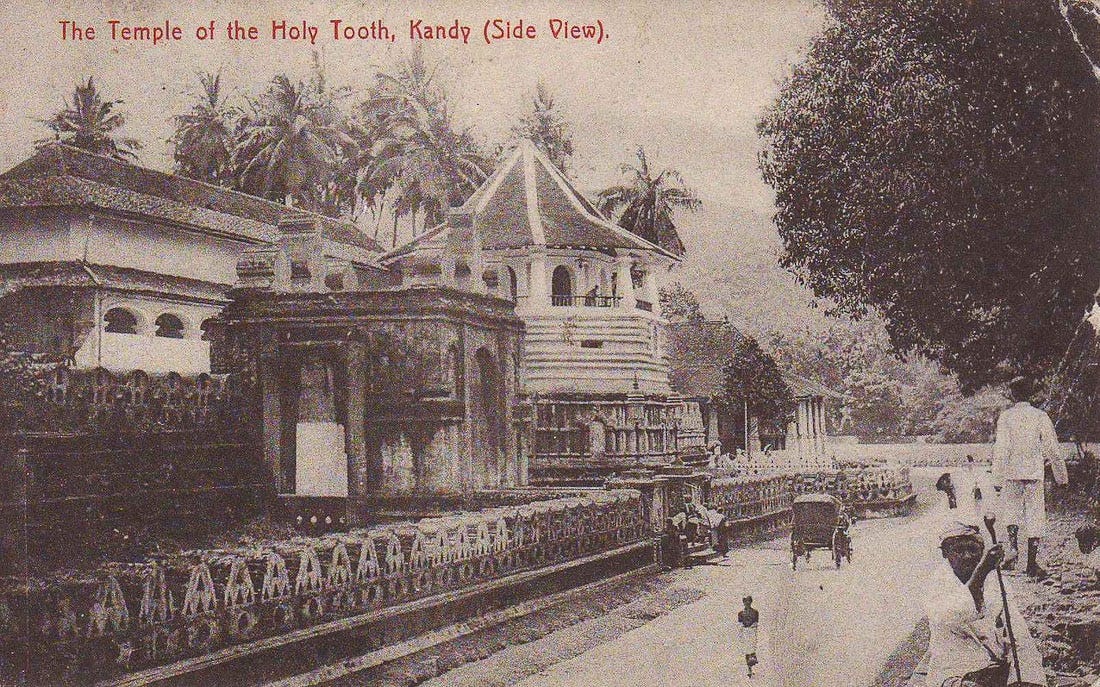

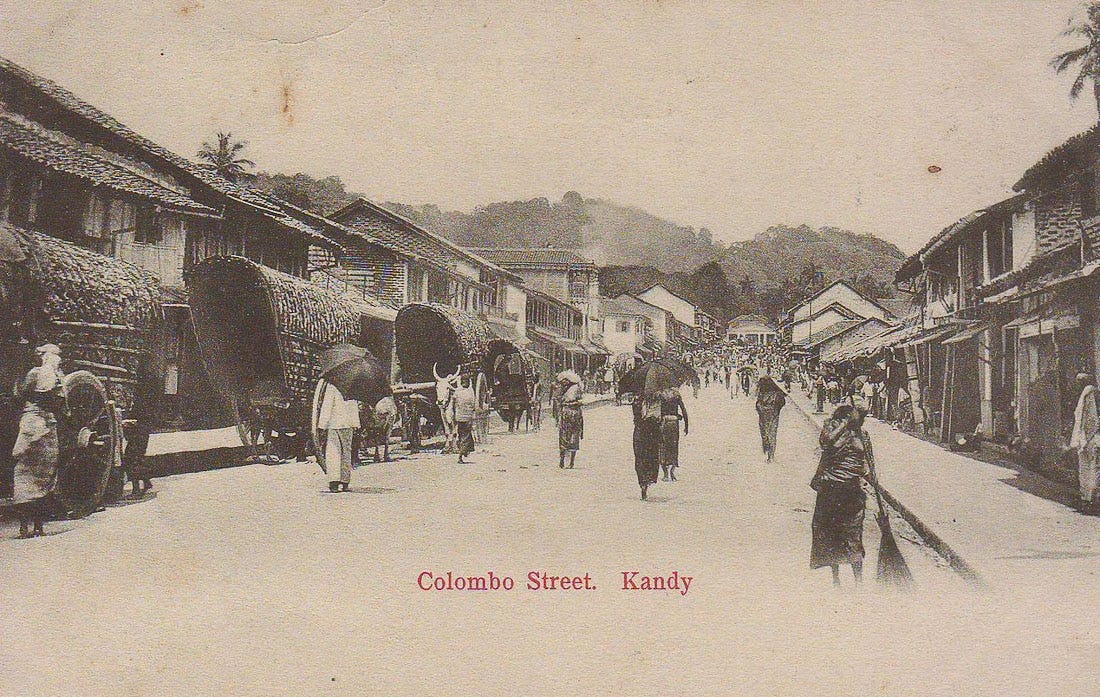

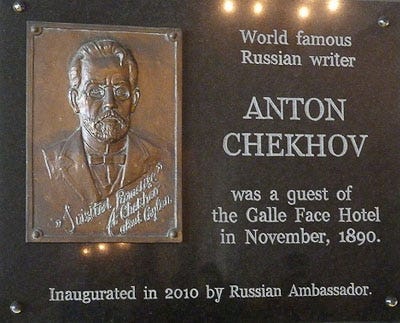

After leaving Blagoveshchensk, Chekhov eventually reached the island of Ceylon, a tropical "paradise on earth." Here, too, new impressions awaited him, including erotic ones. In one of his letters from Ceylon (end of 1890), Anton Pavlovich broke into a whole hymn to sensual pleasures:

Here, in paradise, I have satiated myself up to my throat with palm forests and bronze women."

...

I will open a harem for myself, in which I will have naked large women with buttocks painted with green paint.

And soon, Chekhov delivered that very phrase that often shocks admirers of his "proper Chekhovian image":

When I have children, I will not without pride tell them: "You sons of bitches, in my lifetime I had relations with a black-eyed Hindu woman... and where? In a coconut forest, on a moonlit night!

By the way, from his distant travels Chekhov brought back not only vivid memories but also a mongoose named Bastard6. The pet would tear around the house, breaking pots and tugging at the beard of Chekhov's elderly father, until he finally went completely mad and ran off into the Kaluga forests. Anton Pavlovich, bidding farewell in a letter, even sadly noted: "Without Lika7, his sister, and the mongoose, Anton was sad and lonely."

In 1901, at the age of 41 and gravely ill with tuberkulosis, Chekhov married Olga Knipper, an actress from the Moscow Art Theatre. Chekhov met Olga Knipper in 1898 during rehearsals for his play "The Seagull" at the Moscow Art Theatre. Unlike his previous fleeting romances, their relationship developed gradually through letters and occasional meetings. Olga was not merely another admirer but a talented actress who understood his work profoundly. Their correspondence blossomed into a romance despite Chekhov's deteriorating health and his habitual wariness of commitment. She became his confidante, creative partner, and eventually his wife. Stanislavsky, the theatre's founder, would later note that Olga brought joy and light into Chekhov's final years, something his many previous admirers had failed to do. Their wedding was conducted in secret, with only a few witnesses present—a decision that reflected Chekhov's lifelong preference for privacy in personal matters. But even in marriage, Chekhov remained true to his habit of describing events with a gentle smile. There is a well-known episode from the couple's letters: when Olga received leave in 1902 and came to her husband in Yalta, they spent five days practically without leaving the bed. "Five days we spent naked and indulged in amorous pleasures," Chekhov candidly shared in a letter to a friend. And when Olga left to return to her tour, the writer humorously summed up this "kavardak" with the phrase: "When you left, antonovki appeared on the threshold."

The illness progressed, and in 1904 Anton Pavlovich died in Olga's arms.

After Anton Pavlovich's death, his loyal sister Maria carefully edited her brother's archive, trying to protect the genius's reputation from scandals. Many compromising fragments of letters were struck out with purple ink or hidden by her. Then came the time of editorial and censorship amendments. For example, words that were commonly used in Chekhov's time but later shifted into the category of obscene vocabulary were removed from the letters. In the 1970s, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union censored letters of a "frivolous" nature, with the Politburo even issuing a decree "Against the Vulgarisation and Discreditation of Chekhov." Only decades later did philologists restore some of these texts, and descendants got to know "another Chekhov", not just a good doctor and humanist, sharp-tongued mocker, but also one who could sometimes drink, swear, visit a prostitute, quarrel with relatives, or fall into despondency. But does this diminish his contribution to literature? Rather the opposite—it makes him literary. Chekhov, like his characters, turned out to be a person both contradictory and whole at the same time. In him, the highest decency and earthly weaknesses were amazingly combined, "the high mixed half-and-half with the low". He did not judge anyone from on high because he himself was not an angel and understood this perfectly. Perhaps that is why his prose is permeated with a gentle smile, that very saving irony, a tender mockery of an imperfect world. "Chekhov without the pince-nez" can laugh, dash off to a friend another outrageous anecdote about the "bronze women of paradise," tease an offended lover in a letter, and be bored in the countryside (or Europe), but with all that he can treat sick peasants, build a school in Melikhovo, and of course forever change literature. This is what he is—the real Anton Chekhov, who was not afraid to be frank, as he wrote about himself: "I never hide," "I never lie."

Anton Pavlovich said that "If there are no facts in life—compose something lyrical." In the case of his own biography, there is no need to make anything up—Chekhov's life is much brighter than any legend, one need only unshackle it from conventions. In it, there was room for everything: both high feelings and primal passions, and between them—the kind smile of an author ready to understand and forgive human weaknesses. Chekhov did not live long, but managed to "have his fill of roaming and sinning", which he told his close ones about. And now, reading these lines across a century, we seem to hear his quiet chuckle from behind history's curtains. The stage darkens, the candles go out... But Chekhov's words, daring, ironic, alive, continue to sound, promising: all is forgiven to a person as long as you have humour and a thirst for life.

Other names include (but not limited to): Vanyusha, Vanyushka, Van’ka, Vanyok, Vanyushenka, Ivanushka…

Almost like yours truly, for that matter.

"Houses of tolerance" (doma terpimosti) was the official bureaucratic term for regulated brothels in Imperial Russia. Following the reforms of 1843-1844, prostitution was legally tolerated under police and medical supervision, with establishments being granted official permits. Patrons included men from all social classes—from students and merchants to aristocrats—with different establishments catering to different clientele. This system continued until 1917 when the Provisional Government closed all such establishments. The euphemistic name itself—"houses of tolerance"—reflects the Empire's pragmatic yet somewhat hypocritical approach.

"Kavardak" (кавардак) is a colorful, yet perhaps too literary, Russian colloquialism denoting chaos or disorder, but with distinct connotations of revelry and sensual confusion rather than mere disorganization. Dating back to 18th century merchant slang, it likely derives from Turkic "kavurdak" (stir-fry) ,a jumble of ingredients tossed together (probably). I decided to leave it like that because "mess" is nowhere near and because why not. Perhaps, we could use "bacchanalia" or "shenanigans", which both feel similar, yet connotation of kavardak for me is somewhat in between those two.

Konstantin Apollonovich Skalkovsky (1843-1906) was a Russian mining engineer, traveler, and writer known for his cosmopolitan lifestyle and somewhat scandalous reputation. The photograph Chekhov references—allegedly showing Skalkovsky with a Japanese prostitute—had become notorious in Russian intellectual circles.

The original name is "Сволочь" (Svoloch), a rather strong expletive in Russian that literally means "rabble" or "riffraff" but functions as a harsh insult closer to "scum" or "wretch." "Bastard", though, similarly conveys an insult that can be repurposed as a grudgingly affectionate nickname

Lydia (Lika) Mizinova (1870-1937) was a close friend of Chekhov, with whom the writer was once in love. Their relationship did not work out, but they maintained friendship and correspondence. Lika became the prototype for Nina Zarechnaya in Chekhov's play "The Seagull".