Truth Crawling Back to Her Well

On naked Truth, art, recurring symbols, and proximate points on the historical helix

There was a period in history when the world found itself caught in paradox and shrank by expansion. This era witnessed a surge in globalisation and rapid technological advancements, such as the widespread adoption of revolutionary communication technologies that altered the way people connected, travelled, and traded. Society changed under growing urbanisation, shifting gender roles, the rise of consumerism, increasing nationalistic and populist sentiments, as well as geopolitical conflicts, tensions, and shifting power dynamics. Simultaneously, significant advancements in media technology made capturing and sharing everyday life, travel, and social documentary more accessible to the masses. This led to an increased interest in these subjects and gave birth to new forms of mass media, which irreversibly transformed the way information was consumed.

But the key aspect of this epoch is not merely that the world changed, but rather the consequences of those changes, which themselves had not yet happened. Instead, there was an anticipation of something even bigger, a widespread feeling that the old order was crumbling, but the shape of the new was yet to be determined.

The time period I am referring to is none other than the 1890s, as you might have guessed.

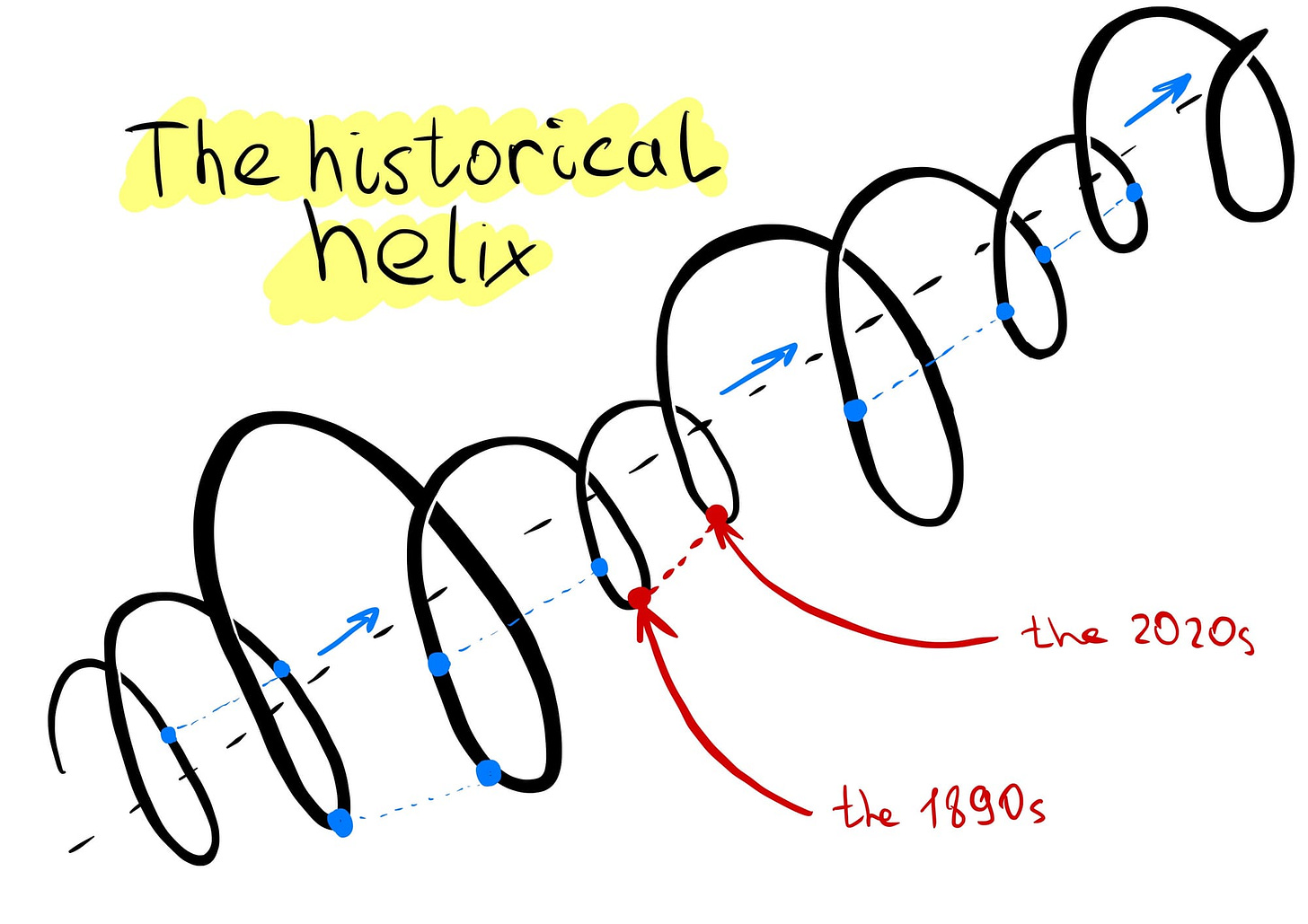

People say that history repeats itself, rhymes, echoes, acts as a mirror or whatever it is it often does, but let's shove those metaphors somewhere dark. It never does perfect circles, the rhymes are always sluggish, and the mirror often shows you what you ask it to show. Instead, let's call it a helix—the historical helix. On that spiral or spring, nothing's ever the same, but there are periods of slow movements and rapid turnovers that are dimensionally closer to the previous rings. And, because it's a helix, there are always such periods. Being at any given point, we feel that certain points in the past are closer to us than others. Two diametrically opposed points on the circumference of one ring of the spring are further apart than many points on the other rings down below its curvature. There are events, conflicts, and issues that keep resurfacing throughout history again and again with new relevance, often startlingly new, sometimes having dramatic consequences. And there are recurring themes, images, metaphors, symbols, and archetypes from the past that resonate more at certain periods of time, losing their old meanings and acquiring new ones, as we look at them from new places and new angles. This is how I believe it works not only in historical memory but in personal memory, too.1

One such recurring image is the personification of Truth. In the late 1890s, Jean-Léon Gérôme, an important figure in French art history, made several paintings portraying her. Each painting was a standalone piece of art, yet considered together, they tell a curious story about the time in which Gérôme lived—a story we're going to consider today.

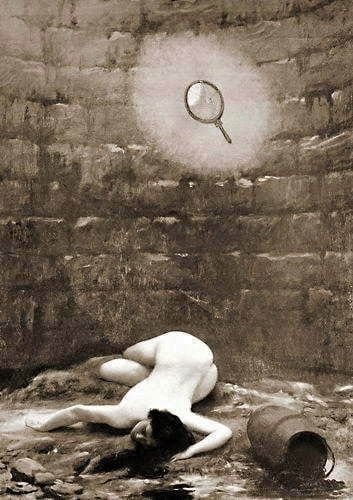

The first painting was called "The Nurturer Truth Lies in a Well, Having Been Killed by Liars and Actors" (from Latin, Mendacibus et histrionibus occisa in puteo jacet alma veritas) and showed the consequences of a brutal reprisal of Falsehood against a woman in the allegorical image of Truth, lying murdered at the bottom of a well with "the mirror above her, from which flashes of light are cast as it lightens the dark abyss"—which is, in turn, supposed to represent a reflection of reality, something that exposes said Truth.

The first question is, why is she in the well? Well, the imagery traditionally originates from a translation of Democritus's aphorism, "Of truth we know nothing, for truth is in a well" (eteêi dè oudèn ídmen: en buthôi gàr hē alḗtheia) and is meant to symbolise its hidden nature. In Greek mythos, the personification of truth was Aletheia, a daughter of Zeus in some accounts and a creation of Prometheus in Aesop's Fables. The word "Aletheia" can also mean "unconcealedness", "disclosure", "revealing", or "unclosedness" as an antonym to lethe, "oblivion", "forgetfulness", "concealment". Literally, aletheia means "the state of not being hidden; the state of being evident", but it can also mean the factuality of reality.

Truth was depicted both as a woman dressed in white and as a nude woman holding a hand mirror, in both cases symbolising that she is "unconcealed", "disclosed", and "revealed", just as she herself "unconceals", "discloses", and "reveals" the truth.

Created right before the 1890s, Klimt's painting "Nuda Veritas" also portrayed Truth using the exact same symbols (plus a snake), as if such an image of Truth had resurfaced in the cultural context of that time and regained its life. In this painting, there is a particular emphasis on femininity that encourages the viewer to think of her as beautiful and desirable, as the capital "T" Truth is for many, rather than just as an allegorical figure.

Gérôme and Klimt belonged to different artistic circles, and after doing quick search, I couldn't find any record of whether Gérôme saw or commented on Klimt's painting. Yet he used the same symbols, which we can thus deem as universal and known to many European artists of different backgrounds at that time. But in Gérôme's work, Truth, despite also being nude and having a mirror, isn't portrayed as desirable. Why is Gérôme's Truth lying murdered?

There are several reasons, which are considered debatable by art historians, so allow me to elaborate by providing two main hypotheses that are also vivid attributes of that time. Whatever the true reason is, consciously or not, the painting is a reflection of that past reality, the artist's perception of it, and his commentary on the state of affairs in the 1890s.

Gérôme was a staunch defender of the academic tradition (his style is often referred as "academicism"), which favoured classical techniques, historical subject matter, and a highly polished, realistic style. He was, which I'll also mention later, doing what photography had begun doing at the same time, but with oil on canvas. He was against Impressionism in art, whose adherents preferred to focus on light, colours, and shapes rather than realism. Their paintings seemed unfinished to Gérôme, and he called them "pretentious", "inane", and "junk". As a powerful and influential figure in the French art establishment at that time, Gérôme used his position to oppose the Impressionists and other avant-garde movements, advocating instead for a return to traditional academic values and techniques. He caused scandals and objected to several Impressionist exhibitions, including Manet's memorial exhibition, though he still attended it and later mentioned it was "not as bad as he thought."

In the same decade, at the end of 1894, the Dreyfus affair divided France when Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a French artillery officer of Jewish descent, was wrongfully convicted of treason for allegedly communicating French military secrets to the German Embassy in Paris. The scandal lasted twelve years and reached such heights in French society that no artist could stand on the sidelines and make no statement.

Gérôme presented the painting of Truth lying at the bottom of the well at the Champs-Élysées Salon in 1895. In the same year, perhaps earlier, he painted another work using the same symbols, where Truth is alive and looking up, illuminating the well with a mirror.

And one year later, he presented another painting, "Truth Coming Out of Her Well to Shame Mankind" (from French, "La Vérité sortant du puits armée de son martinet pour châtier l'humanité"), which is even more powerful and striking and the most acclaimed and well-known. The curator of the Musée Anne de Beaujeu in Moulins, where the painting has been on permanent exhibition since 1978, even said, "C'est notre Joconde à nous." ("This is our Mona Lisa.")

It is the same woman, but now she's emerging from her well. She doesn't have a mirror anymore and instead holds a whip. Her facial expression is complex; it's angry, passionate, and ready to shout at the viewer, making it impossible not to feel awkward. Again, why is she coming out of her well? Why is she raging, and why does she want to punish humanity?

Given that she's Truth, the obvious answer is that it's because of our misconceptions and delusions—everything that is lethe. Gérôme's message behind it is, however, debatable. All the mentioned paintings have been suggested to relate to the Dreyfus Affair in one way or another. Some say that the last painting, where Truth emerges from the well, is Gérôme's direct reaction to it. He presented the painting after Dreyfus's imprisonment on Devil's Island and the emergence of evidence that the real culprit was Ferdinand Esterhazy. Truth was now "known", and thus she came out into the world to punish those who hadn't listened before. In terms of composition, symbols, and ideology, the painting is similar to the work by Debat-Ponsan that was dedicated to the Dreyfus Affair. Could we say it was a flashmob?2

Conversely, other art historians say that all of the mentioned paintings were part of Gérôme's diatribe against Impressionism rather than a direct commentary on the political scandal. The painting fits themes of visual revelation and truth and the way reality is perceived and portrayed. To Gérôme, any distortion of it, both in art and news, would be equal to misinterpretation of the truth about the world, which was important to him as an artist, as an active member of French society, and as a human being. When he died in 1904, as one of his biographers wrote, "the maid found him dead in the little room next to his atelier, slumped in front of a portrait of Rembrandt and at the foot of his own painting, Truth." It wasn't specified which painting it was.

Gérôme's strong belief in the importance of truth and accuracy in art was not limited to his paintings alone. He wasn't conservative in everything and recognized the potential of new technologies. In a preface for Le Nu Esthétique, in 1902, two years before his death, Gérôme applied the same metaphor of Truth emerging from the well to photography, which had seen a significant rise in the 1890s after the introduction of the Kodak camera in Europe earlier. "Photography is an art," wrote Gérôme. "It forces artists to discard their old routine and forget their old formulas. It has opened our eyes and forced us to see that which previously we have not seen; a great and inexpressible service for Art. It is thanks to photography that Truth has finally come out of her well. She will never go back."

"But where is she then?" We can ask now, more than 120 years later, being again at a close point on the historical helix, after the world has undergone two world wars, a dozen of revolutions, rise of radio and television, invention of a computer and the internet, and many other radical cultural, societal, and technological shifts, and is still in seemingly infinite flux.

To answer the question, let's turn to the stranger-in-town trope. Imagine Truth emerging into the modern world from her well and walking around. Devil-like figures, such as Woland in Mikhail Bulgakov's "Master and Margarita" or Irimiás in László Krasznahorkai's "Satantango", arrive in the real world to wreak havoc and expose the weaknesses and flaws of society, revealing their corruption, selfishness, hypocrisy, greed, and moral decay, whether it's the Soviet capital or a run-down Hungarian village. Or John the Savage in Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World", who, raised with traditional values, rebels against the conformist World State society but ultimately finds himself alienated and takes his own life. In a similar situation, what would Truth's heroine journey be?

If we take the definition of truth as "revelation of reality", "unconcealedness", "unobscuredness", we'd see that we have more of it, way more truth than there was in the 1890s. We have so much truth now, we don't know which one is which. It is as remarkable as it is intimidating.

There was a time when most people used to inherit their cultures from their ancestors. For instance, if I had been born in the same Russian village 120 years ago, I would've likely died in the same village believing in the same things as my parents and grandparents. Now, I'm in a place I couldn't've envisioned myself being even ten years ago, writing this to you, reader, in English, which would've also been unfathomable to me at that time. I can study Greek, German, French, Chinese, or whatever philosophy during the day, watch R34 hentai in the evening, argue with a bunch of people from all around the world about some nonsense that happened five minutes ago, or share new premium memes with my friends from Ohio, all while pecking at my phone and laying in bed four thousand kilometers away from the place I was born. I could fly to Tibet tomorrow to become a monk for one month or to South America to live with shamans in the wilderness and eat something utterly hallucinogenic. I could convert to Christianity or Buddhism or the cult of Kek, or start my own cult or a social media group spreading conspiracy theories. All those things and trillions more may seem good or bad or neutral to some, but ultimately they are just there for many of us to pick. Now we're not locked in and not burdened with the legacy; we can pick whatever we want whenever we want. And I firmly believe it is a good thing. I love it; personally, I would be miserable living in the previously only-possible alternative. But, despite such variety providing us more freedom, the amount of choices and the fragmentation of the world has been growing increasingly overwhelming and confusing.

Not even talking about the absolutes, the pursuit of simple truth as factuality of reality is now a daunting task, requiring constant vigilance and critical thinking that many of us lack or are too lazy about. The sheer amount of information available to us every second is beyond the capacity the human brain has evolved to process and handle. We have access to everything that has happened and is happening, whether it's factual or fabricated. The supply of information is now infinite. We don't even need humans anymore to produce it. We can now generate texts, images, video, and audio on demand, whether it's real or hallucinated. Despite all the advantages the technology provides and even higher prospects, just like photography and film in the 1890s, the cost of manufacturing and distributing falsehood, purposefully or accidentally, is now lower than ever, and everyone is so reckless about it. We seem to have the same negligent attitude to the ecology of culture as to the ecology of Earth.

We can see more, yes. Wherever we are, we can see chaos and destruction unfolding in real time on a screen before our eyes. We can witness all the atrocities which even a few decades ago would've been overlooked and hidden in some secret documents. We have access to practically unlimited information, whether it's knowledge or noise. We can talk to people in different countries; we can fight and argue with them, or we can learn about their cultures and beliefs and marvel at the world's idiosyncrasies. We can read news from thousands of sources, from different perspectives, whether it's independent and run by activists, for whom the pursuit of truth is an act of living, or funded and controlled by oligarchs or totalitarian governments, for whom truth is a product of their imagination, the way they want to see reality.

Paradoxically, access to "truth" has made it harder to discern fact from falsehood, as we have to navigate a landscape of competing narratives and alternative facts. It's nearly impossible to convince someone of what is truth and what truth is if they have their own convenient version they have developed over years of meticulous self-deception, wishful thinking, or being brainwashed. Instead of interest and empathy, there's a growing sense of apathy and resignation among many. Faced with a deluge of contradictory information and erosion of trust in institutions, in reality itself, some have simply thrown up their hands and embraced a post-truth mentality, where personal beliefs and emotions trump objective facts. Others have decided to ignore that reality, lock themselves away, and not participate, thereby trusting their lives to institutions they claim they don't trust anymore.

Looking at all that, what would Truth see?

She would see so overwhelmingly much. She would face so many doppelgängers of herself she would be horrified and doubt herself. She would see the manipulative and corrupt media, echo chambers, fake news, deepfakes, engagement over accuracy, feedback loops that reward sensationalism and misinformation. She would see paparazzis chasing her and then editing her image to the most nudest levels. She would see how reckless we are about truth, how we allow others to orchestrate reality for us, how people trust senile madmen with nukes more than their own families.

And what would she do? Perhaps she would jump off the Golden Gate Bridge because "one Reddit user suggested that", or she would run away, crawl back to her well, to the bottom, and hide there. Perhaps she already did that years ago, for now she's nowhere to be seen. Though the question is not where Truth is, but who will help her to return on the historical helix to unleash her revenge.

I’ve written a short story applying the helix metaphor to personal perception of memory. It’s called Helix, and you can read it on my website. “Imagine. Simultaneously you experience the past, the present, and the future, and not only experience but change them. You're here, in the infinitesimal present, sandwiched between two strata of time — the past and the future. The memories, they shape you, and you, in return, review and reshape them, until there's nothing left of what really happened, and instead only what the present you have created for yourself — the time never been.”

Probably not, they didn't have the word flashmob back then.

Brilliant history and thought experiment. The opening completely hooked me. I love the question, What is truth’s heroine’s journey? I can already tell this will stay with me all day.

Analisar a trajetória da arte evoluindo sob a perspectiva do tempo helicoidal, diferenciado do ponto de vista linear - o tempo como uma seta lançada para o futuro -, traz novos elementos ou detalhes possíveis de explicar nossa confusão cognitiva neste século 21, onde os fluxos de informações caminham em volumes e velocidades incríveis, comprimem o espaço-tempo, a ponto de falsidade e verdade se tornarem indiscerníveis, tornando tudo passível de suborno. De Demócrito à Gérôme, que em 1895, pinta a Verdade como "assassinada pelos mentirosos e atirada no poço escuro", as tintas da situação da verdade se embaralham. Já em 1898, Édouard Debat-Pousan a retratou tentando sair do poço, mas sendo cruelmente agarrada e impedida pelos seus algozes. Aqui em 2024, Bansky (?) a representa se arrastando de volta ao poço, humilhada. Melhor impossível. Confesso que também eu, busco o "artista da história", mas não o faria com tal brilhantismo. Genial.