Psychology of Creativity

my translation of Zamyatin's lectures "How to Write Stories": Part I (not sure there're gonna be more parts, but let's be optimistic, shall we?)

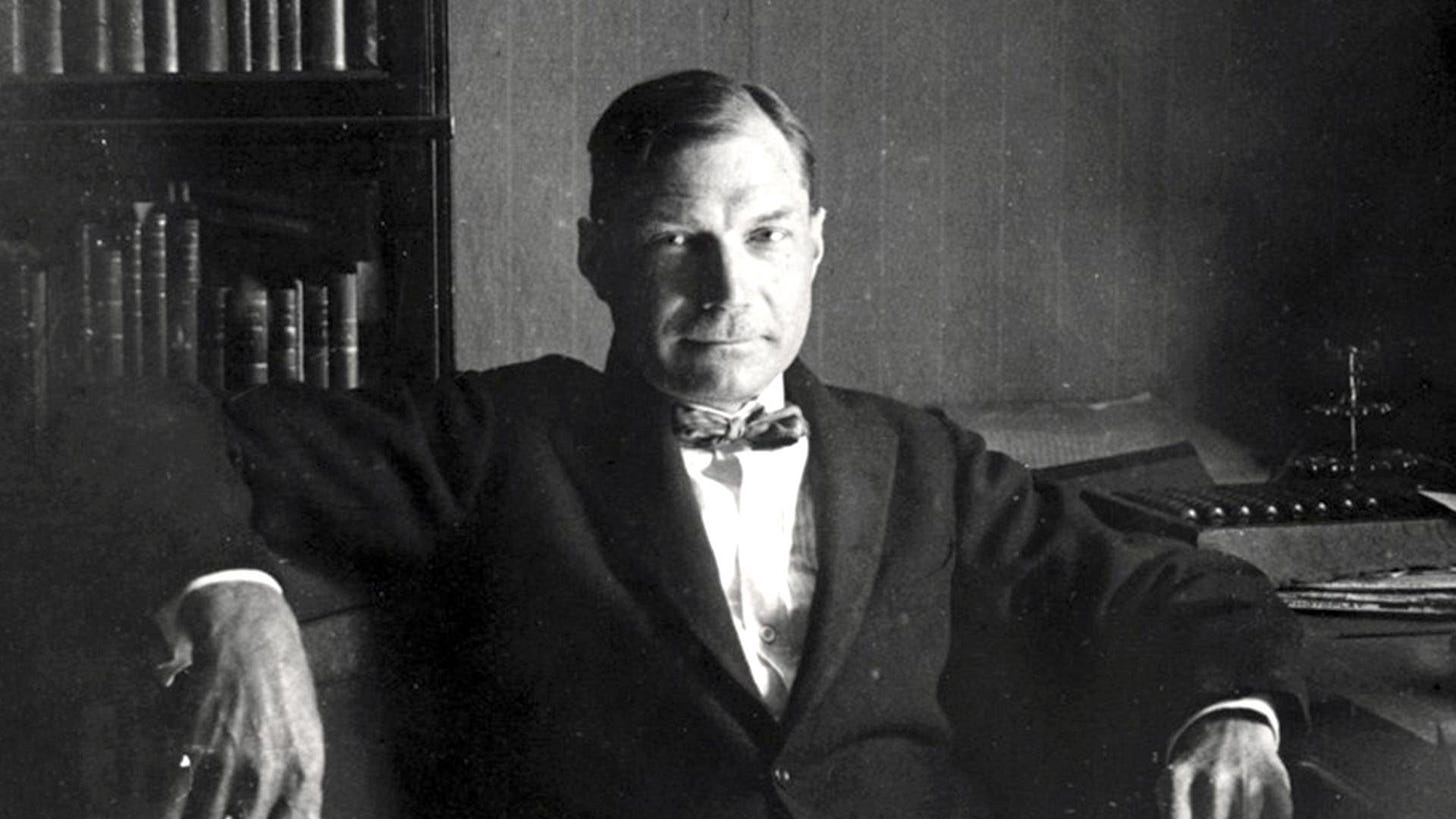

Yevgeny Zamyatin, a figure of profound significance in 20th-century literature, is renowned not only for his literary prowess, such as the dystopian novel "We" that later inspired many other works in the same genre, but also for his stance on censorship, creative freedom, and keen understanding of the artistic process. Years before it led him into self-exile, in the wake of the Russian Revolution, Zamyatin delivered several lectures to young literati at the literary studio of the House of Arts in Petrograd.

"In 1917 he returned to Petersburg and plunged into the seething literary activity that was one of the most astonishing by-products of the revolution in ruined, ravaged, hungry, and epidemic-ridden Russia. He wrote stories, plays, and criticism; he lectured on literature and the writer's craft; he participated in various literary projects and committees – many of them initiated and presided over by Maxim Gorky – and served on various editorial boards, with Gorky, Blok, Korney Chukovsky, Gumilev, Shklovsky, and other leading writers, poets, critics, and linguists. And very soon he came under fire from the newly 'orthodox' – the Proletarian Writers who sought to impose on all art the sole criterion of 'usefulness to the revolution.'"

— Mirra Ginsburg about the 1919-1921, the period in Zamyatin’s life after he returned from his first exile in England, where he worked as a naval engineer for several years.

I decided to translate some parts of his lectures that I found most interesting, add some footnotes, including graphical and extra quotations.

The today’s lecture, first read in 1919 and later published in "Works" Vol. 4 in Munich in 1988 and in "Literary Studies" in 1988, represents Zamyatin's first foray into the seminar "How to Write Stories" where he was a principal lecturer. The primary goal was the literary education of young poets and fiction writers together with other luminaries mentioned by Ginsburg in the quote above.

The lecture is rich with brilliant and honest thoughts on creativity and craftsmanship and full of unique parallels and artistic references, which makes it not just a lecture but a historical document, reflecting the intellectual milieu of that time.

Shall we?

FYI, Substack says this post is near email length limit (due to additional media), so I reckon it’s better be read in browser.

In surgery, there is a division into major and minor surgery: the former is the art of performing operations, and a good surgeon can only be someone with a talent for it; the latter is a craft, and anyone can learn to apply dressings and dissect abscesses.

Astronomy also divides into major and minor: the latter being that part of applied astronomy necessary, for instance, to determine a ship's position at sea, to check a chronometer by the sun, etc.

I see the same division in the arts. There is major, great art and minor, lesser art, artistic creation and artistic craft. Only Byron could write "Childe Harold" but anyone can translate "Childe Harold" if they attend a course... Only Beethoven could write the "Moonlight Sonata"; many can play it on the piano — and do it well. Writing "Childe Harold" and the "Moonlight Sonata" is artistic creation, the realm of great art; translating "Childe Harold" or playing the "Moonlight Sonata" is in the realm of artistic craft, minor art. And it is quite clear that while one can teach minor art, the artistic craft, one cannot teach great art, artistic creation: one cannot be taught to write "Childe Harolds" and "Moonlight Sonatas".

That is why I renounce the title of my course from the very beginning. It is impossible to teach how to write stories or novels.

What, then, shall we do? — you ask. — Is it better we part and go home?

I answer: no. We still have something to do.

Minor art, the artistic craft, is invariably a component of great art. Beethoven, to write the "Moonlight Sonata", had to first learn the laws of melody, harmony, counterpoint, that is, study the musical technique and the technique of composition belonging to the realm of artistic craft. And Byron, to write "Childe Harold", had to study the technique of versification1. Similarly, anyone aspiring to creative work in the field of artistic prose must first learn the technique of artistic prose.

Art evolves, obeying the dialectical method I discussed last time2. Art works pyramidally: at the base of new achievements lies the use of everything accumulated there, at the bottom, at the foundation of the pyramid. There are no revolutions here, more than anywhere else — only evolution. And we must know what has been done in the field of the artistic word's technique before us. This does not mean you must follow old paths: you must contribute your own. An artistic work is only valuable when it is original both in content and form. But to leap upwards, one must push off from the ground, so there must be ground.

There are no laws on how to write, and there cannot be: everyone must write in their own way. I can only tell you how I write, how people generally write. I can say not how one should write but how one should not.

Thus, the main subject of our work will be the technique of artistic prose. For those with a creative flair, this will help them emerge quicker from their shell; for those without, these lessons can still be interesting, can provide some information in the field of the anatomy of artistic word works. Useful for critical work. Those with a voice need proper 'voice training,' as singers call it. That is the second task. But those without a voice, of course, cannot be taught to sing.

If I were to seriously promise to teach you to write stories and tales, it would sound as absurd as if I promised to teach you the art of loving, falling in love, because that too is an art, and it also requires talent.

I took this comparison not by chance: for an artist, creating any image means being in love with it. Gogol was certainly in love — not only with the heroic Taras Bulba but also with Chichikov, Khlestakov, the lackey Petrushka3. Dostoevsky was in love with the Karamazovs4 — all of them: the father and both brothers. Gorky in "Foma Gordeyev"5... well, the figure of the old man Mayakin was supposed to come out as a negative type: he is a merchant. I remember perfectly: when I wrote "Uyezdnoye,"6 I was in love with Baryba, Chebotarikha — no matter how ugly or monstrous they were. But there might be beauty in monstrosity, in ugliness. Scriabin's harmony, in essence, is monstrous: it consists entirely of dissonances — and yet it is beautiful. Coincidence with [Alexader] Blok...

I speak of this not to prove the axiom that one cannot be taught creativity, but to describe to you this process of creativity — as far as it is possible and as far as I am familiar with it from my own experience.

Just like falling in love, it is simultaneously a joyful and torturous process. Perhaps an even closer analogy is with motherhood. No wonder Heine in his "Gedanken"7 has such an aphorism: "Every book must have its natural growth, like a child. An mother is not supposed to give birth to her child before nine months."8

This analogy is the most natural: because, after all, a writer, like a mother, creates living people who suffer and rejoice, mock and amuse. And just as a mother her child, a writer creates his people from himself, nourishes them with himself — some immaterial substance contained in his being.

We have little material to grasp the very process of creativity. Writers seldom speak of it9. And that's understandable: the creative process mainly takes place in the mysterious realm of the subconscious. Consciousness, ratio, logical thinking, plays a secondary, subordinate role.

In moments of creative work, a writer exists in a hypnotised state: the consciousness of the hypnotised person perceives and develops only those impressions that the hypnotiser provides. You can pinch, prick the hypnotised subject, let them smell ammonia – they won’t feel a thing. But let the hypnotiser come, give them a sip of water, and say, "This is champagne" – and immediately all associations, taste and emotional, connected to champagne appear in the subject’s mind: they declare their delight, describe the taste of champagne, and so on. In short, creativity emerges. But as soon as the consciousness of the hypnotised is freed from the will of the hypnotiser – the creativity ends: from water, one can no longer create wine, no longer perform this miracle of Cana in Galilee10.

I often thought that under hypnosis, a writer could write ten times faster and easier. Unfortunately, no experiments have been conducted in this direction. The difficulty of creative work lies in the fact that the writer must combine both the hypnotiser and the hypnotised within themselves, must hypnotise themselves, lull their own consciousness, and this, of course, requires a very strong will and a very vivid imagination. It is no wonder that many writers, as is known, resort to narcotics during work to dull the conscious mind and enliven the subconscious, the imagination. Przybyszewski couldn't write without cognac in front of him; Huysmans, and not only he, used opium, morphine for this purpose. Andreyev drank the strongest tea while working. Remizov, when writing, drinks coffee and smokes. I can't write a page without cigarettes.

The behaviour described by Zamyatin above mirrors the ideals of Decadent movement in literature. Decadence, flourishing in the late 19th century, was characterised by a fascination with the morbid, the irrational, and the sensual, often exploring the idea of art superseding the mundane realities of life. Writers like Charles Baudelaire delved into these themes, believing that beauty often resides in the unconventional or the grotesque. In his Le Spleen de Paris, also known as Paris Spleen or Petits Poèmes en prose, he wrote:

“You have to be always drunk. That's all there is to it—it's the only way. So as not to feel the horrible burden of time that breaks your back and bends you to the earth, you have to be continually drunk.

But on what? Wine, poetry or virtue, as you wish. But be drunk.

And if sometimes, on the steps of a palace or the green grass of a ditch, in the mournful solitude of your room, you wake again, drunkenness already diminishing or gone, ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that is flying, everything that is groaning, everything that is rolling, everything that is singing, everything that is speaking. . .ask what time it is and wind, wave, star, bird, clock will answer you: "It is time to be drunk! So as not to be the martyred slaves of time, be drunk, be continually drunk! On wine, on poetry or on virtue as you wish."

All this, I repeat, is to dull the work of the consciousness, to subordinate it to the subconscious. An attempt to analyze the creative process inevitably leads to consciousness coming to the forefront, the hypnotised awakens, the creative work stops, and therefore, so does the analysis. I have tested this on my own experience. This explains why we find so few indications from writers about how the creative process unfolds. We only find vague indications that writing is hard, or joyful, or torturous.

Chekhov in a letter to L. Gurevich11: "I write slowly, with long intervals. I write and rewrite – and often, without finishing, I throw it away". In another letter: "I write and cross out, write and cross out". In his last years, he no longer wrote, but as he jokingly said about himself – "drew" (with red ink).

We know what the manuscripts of Tolstoy, Pushkin look like: many corrections and variants – and, therefore, many creative torments.

Maupassant. "Strong as Death" (Fuerte Como La Muerte). In the second part of the novel, almost every phrase was changed and reconstructed. The final phrase – 5 variants! This was written already in the period when Maupassant's illness was increasingly affecting him. The phenomenon I spoke of is clearly felt here: the author is unable to hypnotise himself, his consciousness; the mind analyses every word, revises, and remodels.

Flaubert. "Salammbô". “For a book to sweat the truth, one must be filled to the brim with the subject. Then begins the torture of the phrase, the agony of assonance, the torment of the period". "I have just finished the first chapter and find nothing good in it, I despair over it day and night. The more I gain experience in my art, the more tormenting it becomes for me: the imagination does not develop, but the demands of taste keep increasing. I suppose that few people have suffered as much for literature as I have." "What a mess of a plot! The difficulty is in finding the right note. This is achieved by extreme condensation of thought, naturally or by force of will, but certainly not by simply imagining a steadfast truth, i.e., a whole history of detailed and plausible facts."

This very "extreme condensation of thoughts" or what I have called self-hypnosis is a necessary and most challenging condition for creative work. Sometimes this state of self-hypnosis, this "condensation of thought," comes naturally, without any effort of will—and this, essentially, represents what is termed inspiration. But such instances are rare. To write something substantial, one must, through some effort of will, reach this state of "thought condensation"—and this cannot be taught: it is some organic ability, which one can only further develop in oneself if it is already present.

The moments of creative work are very much akin to something else: dreaming. In dreams, the consciousness also half slumbers, while the subconscious and imagination work with extraordinary vividness.

The closeness and accuracy of this analogy is evidenced by the fact that, as many writers attest, the solution to one creative problem or another has come to them in dreams. In sleep, Pushkin conceived some verses of "The Gypsies". Hamsun always keeps a pencil and paper by his bedside, to jot down whatever suddenly comes to his mind when he wakes in the middle of the night. I myself have noticed that...12

In its ordinary state, human thought operates logically, through syllogisms. In creative work, thought, like in dreams, moves through associations. In relation to a word, object, color, abstract concept being discussed in a story, novel, or tale, a writer experiences a whole swarm of associations. It falls to the consciousness to select the most fitting from these associations. The richer the ability to associate, the richer the author's imagery, the more original and unexpected they are. Hoffman's abundant associational ability makes his stories positively resemble whimsical dreams. Gorky recently read his memoirs about Andreyev and quoted these Andreyev’s words , who also had a rich ability to associate: "I write the word 'cobweb'—and thought starts to unravel, and I think of a real school teacher, who spoke slowly, had a lover—a girl from a pastry shop; he called this girl Milly, but her friends on the boulevard called her Sonya the Bubble."

Look at the rich and whimsical association connected with just the word "cobweb". A writer's creative thought works just like everyone else's in a dream. In sleep, we accidentally touch our throat with the cold pearlescent button on the sleeve. In a normal state, when consciousness soberly works and controls our sensations, this touch of the button will evoke no associations, no emotions. But in a dream, when consciousness is subservient to the subconscious, the touch of the button immediately associates with the touch of a cold steel knife—and in a fraction of a second we see: the guillotine blade—we are condemned to death—in prison—light shines through a narrow window, the lock glimmers—the lock clicks, here comes the executioner, it's time to go...

This ability to associate, if it exists at all, can and should be developed through practice. And this we are going to try. Later, we are going to see that among the artistic techniques—one of the most subtle and most accurately achieving the intended effect—is calculated to provoke in the reader's mind certain associations necessary for achieving a specific, intended impact by the author.

Here is the study and practice of the art of composing verses, which involves understanding the structure, rhythm, and sound patterns of poetry.

It wasn’t the first lecture in the series. The first one was about the state of Russian literature at that moment.

Characters from Nikolai Gogol's works. Taras Bulba is a Cossack hero, Chichikov and Khlestakov are central figures in "Dead Souls" and "The Government Inspector," respectively, and Petrushka is Gogol's character in "The Overcoat."

Central characters in Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel "The Brothers Karamazov," representing different aspects of Russian society and human nature.

Gorky's "Foma Gordeyev": A novel by Maxim Gorky, exploring the life of a merchant and his family, reflecting Gorky's views on the Russian bourgeoisie.

A novella by Yevgeny Zamyatin, originally published in 1912.

"Thoughts" (German) is a collection of aphorisms and brief statements by Heinrich Heine, first compiled and published by A. Strodtmann after the poet's death under the title "Thoughts and Ideas" in 1869. In 1925, a revised and expanded edition was released as part of the volume "Heine's Prose Legacy."

This is a translation of a translation and I’m not sure how correct is it and close to original. I couldn’t find that quote online, unlike many other famous Heine’s quotes, such as “Where they burn books, they will also ultimately burn people.” Given that other quotes in the lecture seem to be also recited by memory, we have no choice but to trust Zamyatin on that.

Oh well, of course they don’t!

Referring to Jesus’s first miracle.

Zamyatin quotes inaccurately from a letter to the editor of the "Northern Herald," L. Ya. Gurevich, dated May 22, 1894.