The Eternal Midwit

introducing and translating Nadezhda Teffi and building bridges between languages and centuries

In the comments to previous translations, Chen Rafaeli brought up Teffi multiple times and nudged me to finally translate some of her works. Even Teffi’s non-fiction featured dialogue and as playful as her short stories, so despite I’m starting with what seems to be non-fiction, you’d be able to very well grasp her voice and sense of humour.

To know each other a bit better, Teffi was the pseudonym of Nadezhda Alexandrovna Lokhvitskaya (1872–1952), one of the most popular and influential satirical writers in early twentieth-century Russia. Many of her contemporaries naturally compared her to Chekhov by saying “Chekhov in a skirt”, which is no surprise in the literary scene dominated by men openly admitting her sense of humour was anomalous for a woman. Early in her career, Teffi herself admitted to be inspired by Chekhov yet developed her own unique voice, mayhap a bit more sardonic, more political, slightly more condescending, than Chekhov’s. “Proving the haters wrong”, she rapidly acquired enormous fame and became a literary celebrity in Russia and beyond and was known, both before and after the Revolution, for her witty feuilletons, humorous short stories, and plays unearthing, admired and beloved by readers of various backgrounds—remarkably, both Tsar Nicholas II and Vladimir Lenin. After the 1917, like many of the big literary figures of that time, Teffi emigrated to Paris, where she also became a central figure in the émigré literary scene. Her keen psychological insight and ability to find humour in human folly made her writing timelessly relevant.

I’m going to share two essays translated by me, one today, "Дураки" (translated by me as “Midwits”, will explain below), and one later this month, “Человекообразные” (“Humanoids”), both explore the same topic of social critique that is so popular nowadays, including on Substack, as means of bridging the proverbial now with proverbial olden days, to see if anything has changed at all and how.

“Midwits” was first published in 1911. In it, Teffi presciently analyses a particular archetype of intellectual pathology that we might very well recognise today.

Before we begin… A lot of you have joined lately and I’m more than grateful for your interest in my work. However, I couldn’t stick to one type of posts in my newsletter and have been experimenting with the formats, schedules, and what I share here, and want to know what you think. While fiction remains my main endeavour and the whole point of this place, it is called “literary locus” and I do have other interests and I do want to share them too, given how important curation is in our times. So, here’s a short survey just to test the waters:

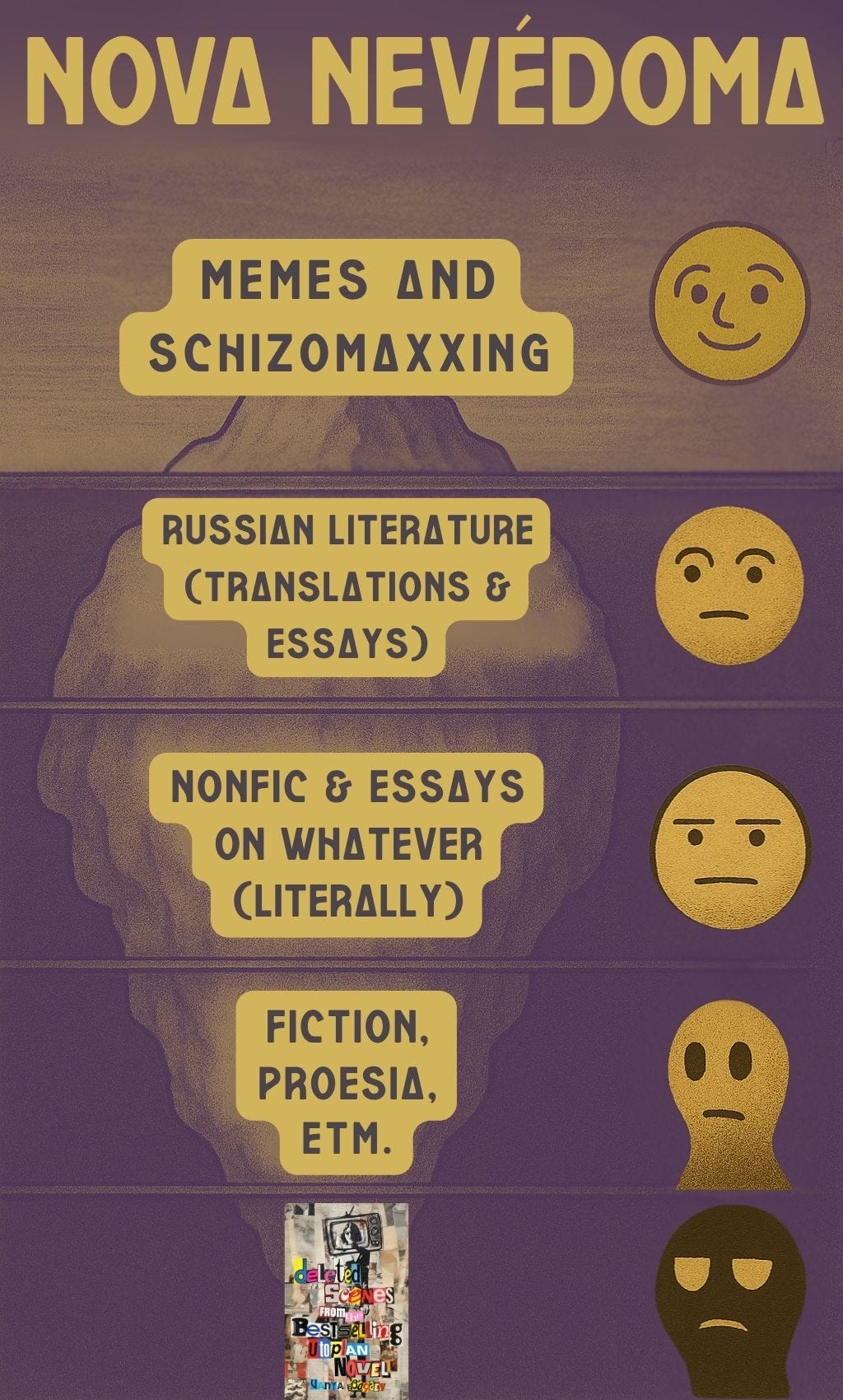

I’ve made this chart a while ago. It’s the best description of what’s going on here so far I could come up with:

Now, to today’s topic… Please enjoy Teffi’s essay and my translation commentary!

Beams of appreciation,

Vanechka

§1 Translation Challenges

The first challenge I’ve never anticipated coming my way was the translation of such a simple word as “durak”, normally understood as ”a fool”. I could’ve translated it as such, or as “an idiot” or mayhap some other synonyms, but none would’ve really worked because Teffi in her essay uses “durak” not simple as the word for a stupid, non-intelligent person but for a person with systematic and limited thinking, a person who pretends to be an intellectual. I’m not sure if it’s some old meaning of “durak” or her own interpretation—it’s been more than a hundred years since she wrote it, many things must’ve changed. Etymologically, the words semantic networks spreads across foolishness, juniority in the family, and even the protective function of the name-herald. Its root in Indo-European languages meant “sick, bitten, stung”, later it evolved into “a jester”, “a holy fool”, and only then it started being used as “a fool”. Its current meaning implies some sort of fatal naivety to that foolishness and does not equates to “an idiot”, yet all of those are different from Teffi’s definition.

In this translation, I have chosen to render "durak" as "midwit"—a contemporary internet term that surprisingly perfectly captures Teffi's insight. The well-known and mayhap worn-out meme of the midwit describes exactly the type of person she was analysing over a century ago: someone who creates elaborate logical systems but lacks the actual wisdom dimwits and geniuses supposedly possess. So, I can allow myself to translate it using a modern word because nobody’s going to stop me and it fits so much better. After reading, you would agree, you won’t be able to unseen that, and you genuinely won’t see any other possible rendition of it. That’s how much eerie the resonance is.

Another difficulty was translating the idiomatic “krugly durak” (round | circular fool), which means “a complete fool”, “an utter fool”. It’s colloquial Russian phrase that Teffi applies a recurring metaphor throughout the essay, crucially so, in the ending. The way I’d translate it would be then “perfect midwit”, similarly to “perfect circle”, and related idiomatic “vicious circle”, which all together I hope should transfer the geometric symbolism to English well. “All round midwit” would mayhap be an option but it does seem to connote mostly positive sentiment.

The said "roundness" in Teffi's usage represents intellectual completeness in a negative sense: systematic thinking that has formed a perfect closed circle, eliminating all gaps, rough edges, and points of entry for genuine inquiry. Her "perfect midwit" is someone who has achieved false perfection through methodical reasoning that endlessly loops back on itself.

So, behold, the midwit meme explained 125 years ago by a wonderful Russian writer…

§2 Midwits

At first glance, it seems everyone understands what a midwit is and why the more midwitted they are, the more perfectly midwitted they become.

Yet if you listen closely and observe carefully, you'll realise how often people make the error of mistaking an ordinary stupid or muddle-headed person for a genuine midwit.

—What a midwit,—people say.—Always got trivial nonsense in his head! They actually think midwits ever have trivial nonsense in their heads!

The thing is, a true, perfect midwit is recognised, above all, by their tremendous and unshakeable seriousness. The cleverest person may be frivolous and act thoughtlessly—a midwit constantly discusses everything; having discussed it, acts accordingly and, having acted, knows precisely why they did it just so and not otherwise.

If you mistake for a midwit someone who acts recklessly, you'll make such an error that you'll be ashamed of it for the rest of your life. A midwit always reasons.

An ordinary person, clever or stupid—it makes no difference—will say:

—Dreadful weather today—oh well, never mind, I'll go for a walk anyway.

But a midwit will reason:

—The weather's dreadful, but I shall go for a walk. And why shall I go? Because sitting indoors all day is harmful. And why is it harmful? Simply because it's harmful.

A midwit cannot bear any rough edges in their thinking, any unresolved questions, any unsolved problems. They settled, understood, and learned everything long ago. They are a reasonable person who will make ends meet on every question and perfect every thought.

When encountering a true midwit, one is overcome by a kind of mystical despair. Because a midwit is the embryo of the world's end.

Humanity searches, poses questions, moves forward—in everything: in science, in art, in life—whilst the midwit doesn't even see any question at all.

—What's all this? What questions are there?

They answered everything long ago and completed the vicious circle.

In their reasoning and circular logic, the midwit relies upon three axioms and one postulate.

The Axioms:

Health is above anything.

If only one had money.

What's the point?

The Postulate: It is what it is.

Where the first three don't help, the last always saves the day.

Midwits generally arrange their lives quite well. From constant reasoning, their faces acquire a deep and thoughtful expression over the years. They love growing large beards, work diligently, and write in beautiful handwriting.

—A solid chap. Not a flighty sort,—people say of the midwit.—Only there's something about him... Takes himself rather too seriously, perhaps?

Having convinced themselves through practice that they've grasped all earthly wisdom, the midwit takes upon themselves the troublesome and thankless duty of teaching others. Nobody advises so much and so earnestly as a midwit. And this comes from the heart, because when they come into contact with people, they find themselves constantly in a state of profound bewilderment:

—Why do they all muddle about, rush around, fuss, when everything is so clear and all round? Obviously they don't understand; one must explain it to them.

—What's all this? What are you grieving about? Your wife shot herself? Well, that was frightfully silly of her. If the bullet had, God forbid, struck her in the eye, she might have damaged her sight. God help us! Health is above anything.

—Your brother went mad from unrequited love? He quite astonishes me. I should never go mad. What's the point? If only one had money!

One midwit I know personally, of the most perfect form, textbook perfect, specialised exclusively in questions of family life.

—Everyone ought to marry. And why? Because one must leave descendants. And why must one leave descendants? Because that's just how it must be. And everyone should marry German girls.

—But why German girls?—they would ask him.

—Because that's just how it must be.

—But surely there won't be enough German girls for everyone.

Then the midwit would take offence.

—Of course, one can turn anything into a joke.

This midwit lived permanently in Petersburg, and his wife decided to send their daughters to one of the Petersburg institutes.

The midwit objected:

—Far better to send them to Moscow. And why? Because it will be very convenient to visit them there. Get on the train in the evening, travel overnight, arrive in the morning and visit them. But in Petersburg, when would one ever get round to it!

In society, midwits are convenient people. They know one must pay compliments to young ladies, that one should say to the hostess:

—You're always so busy with everything,—and besides, a midwit will never spring any surprises on you.

—I'm fond of Chaliapin1,—the midwit conducts polite conversation.—And why? Because he sings well. And why does he sing well? Because he has talent. And why does he have talent? Simply because he's talented.

Everything so circular, so perfect, so convenient. Not a snag or a rough edge. Give it a push and off it rolls.

Midwits often make careers, and they have no enemies.

Everyone acknowledges them as practical and serious people.

Sometimes a midwit even enjoys themselves. But naturally at the proper time and in the appropriate place. Somewhere at a birthday party, perhaps.

Their merriment consists of methodically telling some anekdot2 and then immediately explaining why it's amusing.

But they don't like enjoying themselves. It lowers them in their own estimation.

All the midwit's behaviour, like their appearance, is so dignified, serious, and respectable that they're received with honour everywhere. They're gladly elected as chairmen of various societies, as representatives of sundry interests. Because the midwit is respectable. The midwit's entire soul seems licked smooth by a broad cow's tongue. Circular, smooth. Nothing catches anywhere.

The midwit profoundly despises what they don't know. Sincerely despises it.

—Whose verses were those just recited?

—Balmont's.3

—Balmont? Don't know him. Never heard of such a person. Now I've read Lermontov.4 But I don't know any Balmont.5

One senses that it's Balmont's fault that the midwit doesn't know him.

—Nietzsche? Don't know him. I haven't read Nietzsche!

And again in such a tone that one feels ashamed for Nietzsche6.

Most midwits read little. But there's a particular variety that studies all their lives. These are the stuffed midwits.

This name is quite inaccurate, though, because however much a midwit stuffs themselves, little stays put. Everything they absorb through their eyes falls out through the back of their heads.

Midwits like to consider themselves great originals and say:

—In my opinion, music is sometimes quite pleasant. I'm rather an eccentric, generally!

The more cultured a country, the calmer and more secure a nation's life, the more circular and perfect the form of its midwits.

And often the vicious circles drawn by a perfect midwit in philosophy, or mathematics, or politics, or art remain unbroken for ages. Until someone feels:

—Oh, how dreadful! How circular life has become!

And breaks the circle.

Fyodor Chaliapin (1873-1938): the most famous Russian opera bass of his era, renowned internationally.

Anekdot (анекдот): In Russian culture, this term has a broader meaning than the English "anecdote." While both derive from the Greek for "unpublished accounts," the Russian anekdot developed into a specific short narrative form, often humorous but not necessarily so. Unlike the English understanding of anecdotes as brief personal stories, Russian anekdots are closer to short jokes or tales with punch lines, typically shared orally and passed along through social networks. They're characterised by brevity, often featuring stock characters (like "Vovochka", a mischevious boy, or ethnic stereotypes), and usually end with an unexpected twist.

Konstantin Balmont (1867-1942): leading Russian Symbolist poet, extremely popular in Russia during Teffi's time.

Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841): major Russian Romantic poet, considered a classic figure in Russian literature.

Basically, “reject modernity; embrace tradition” or “classicist vs modernist” divide in Russian literature at that time. Midwits, Teffi writes, aren’t forward thinking and deny the changes in culture while only knowing the “literary giants”, the weight of which in Russian literature of that time was enormous; Futurists even demanded to “throw [them, classics who lived just 50 years ago] off from the Steamship of the Present”. Midwits, Teffi says, don’t read beyond “school curriculum” and only know and show off with the names everybody else also knows and accepts as “trü”. It shows how the midwit's intellectual conservatism isn't really about deep appreciation for classical literature, but about clinging to culturally sanctioned "safe" knowledge. Teffi, however, was neither a hidebound traditionalist nor a radical futurist.

In 1911 Russia, Nietzsche was hugely influential among the intelligentsia, especially the Symbolists and avant-garde. A "midwit" dismissing Nietzsche would signal both ignorance and active resistance to one of the most discussed philosophical figures of the era. You could note how Nietzsche's ideas about individualism and critique of conventional morality were central to Russian modernist thought and we can clearly trace Nietzsche’s influence in Teffi’s writing as well, particularly, in the next essay “Humanoids”. In today’s world, a lot of things have changed and the sides have probably flipped. Nietzsche, from the controversial and rebellious, turned into a classical figure in the Western philosophy, and is, mind you, on any occasion, just like Dostoevsky (still), is name-dropped mindlessly.

Ps just saw the poll. thought it's a multiple choice one. Couldn't go past the first option, consequently. So, a clarification: I'm here for anything.

Can the poll be redone into a multiple choice one? I think it'd reflect things better

Teffi describing a midwit in 1911 feels eerily like watching certain corners of modern Twitter in slow motion. The circle truly remains unbroken.