How to enact generational betrayal

Fathers and Sons, obscure translations, and primordial soup

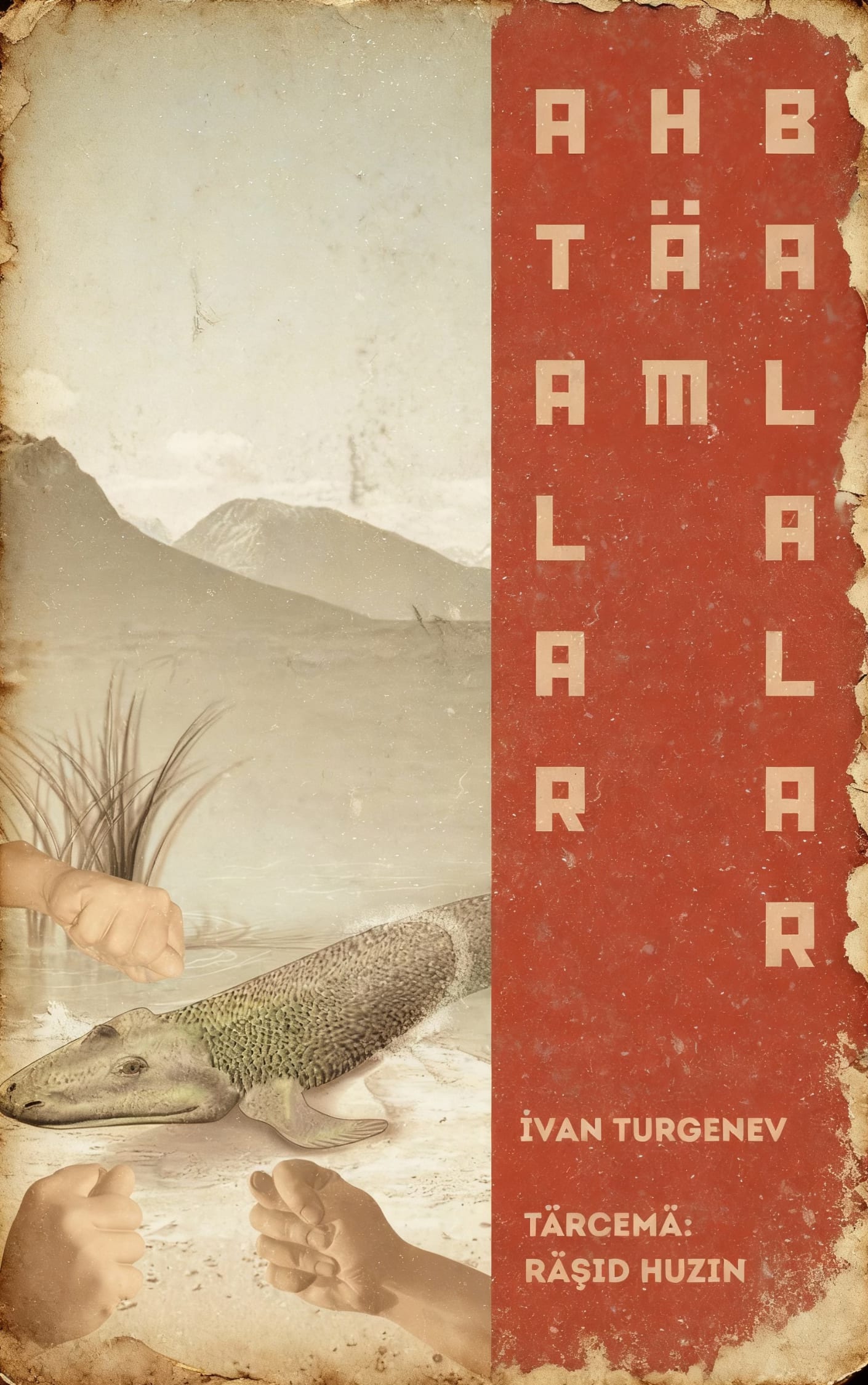

The picture below was intended to be used as a cover to the first Tatar translation of Turgenev’s “Fathers and Sons”. At the time (1928) it was the first literary work in Tatar to use Latin script called Yañalif instead of Arabic script that preceded it, and one of the very few books that managed to use Yañalif before Tatar writing was forced into Cyrillic script (1939), though many baptised Tatars had already been using Cyrillic for centuries.

The book, faithfully titled “Atalar häm Balalar” in Tatar, didn’t become a bestseller and didn’t cause a furore, for everyone in the Soviet Union, especially the intelligentsia — comprised mostly of educated university students, including Rashid Huzin, the translator — already spoke Russian, and those who could benefit from having a Tatar translation of a classic novel were busy breaking their backs in kolkhozes. Despite its innovative, one could now say “meta” approach to translation and artwork, linguistic excellency and mild historical importance, the first Tatar translation of the novel failed to be officially published and for years remained obscure to the public larger than the literary circles at Kazan University, that same university where Tolstoy, Khlebnikov, and Lenin himself studied — Lenin who was expelled for his youthful revolutionary pursuits, yet during the Soviet era the university was nevertheless renamed as Vladimir Ulyanov-Lenin Kazan State University (formerly Imperial Kazan University, now Kazan Federal University).

Rashid Huzin, who paradoxically was an engineering and mathematics student there who fancied the likes of non-Euclidean geometry — Lobachevsky’s legacy, another “revolutionary” from the same alma mater — picked the book so his father, a villager who didn’t read well in Russian, could read the classics so dear to Rashid’s heart, all the more on the dearest of themes: him and his father and a generational and cultural gap between them.

Another reason, of course, was to honour Turgenev’s Tatar ancestry. According to the family legend, Turgenev’s father was of an old noble Turgenev family whose history goes as far back as to the 15th century when Lev Turgen, a Tatar murza (meaning prince, high nobleman, or just a respectable chap), left the Golden Horde to serve Vasily II of Moscow. Later he was baptised and became Ivan Turgenev, the same name his descendant, a great Russian writer, would have a few centuries later.

In this way, Turgenev’s family history mirrors the core premise of his most famous book — parents vs children and past vs present conflict, which is perhaps the core driving force of the joint Russian and Tatar history overall: gaps and shifts between generations, children moving away from their fathers to different geographical, ideological, religious, political planes. Thus Lev Turgen became Ivan Turgenev, another Ivan Turgenev moved to Europe, his character, Bazarov, became a nihilist, a creature incomprehensible for his conservative and Christian father, the Orthodox Russia, both with lower case and upper case O, both in religion and in manners and aspirations, became more “Westernised” (if there’s such a word), and the rift between the said aristocracy and peasantry increased further until it all erupted in 1917. And Rashid Huzin, too, would escape the dual grip of a small Tatar village and his traditional father. As he wrote in the foreword, the chosen commissioned image perfectly depicted that intergenerational dynamic of self-negation, where Self is the continuous fabric of heredity.

“Commissioned” is a bit of a stretch; Rashid’s university friend Fäil Fatihov made it for him for free. As Rashid claimed himself, they were drinking on the night before exams and he had an idea, a vision of how the very first ancestral figure crawled out of the primordial soup and from aquatic to amphibious, from amphibious to Homo sapiens, and further down what Rashid — who clearly sympathised with Bazarov, at least in his youthful fervour — believed to be a path of inevitable descent. Would the ancestral figure’s descendants be thankful to their parent? Should they? Because of what they inherited, or in spite of it? That was the question that tortured Rashid. And then, having that drunken spark of genius, he imagined such a creature before himself, in place of Fäil, and showed him a kukish, known also as a fig gesture1 — a fist with the thumb tucked between the index and middle fingers. Even though the sign historically had the same obscene sexual coital and phallic origins, unlike in many countries, in Russia and in Soviet Union it lost its deeply offensive connotations and often was used as a mocking gesture of rude refusal. The kukish gesture could be performed both by a person and by a book, in which case, as the Russian saying goes, the book would demonstrate it to you on occasions when you desperately attempt to comprehend its content, which it withholds — “You stare at the book and see nothing but a fig”, a proper pre-exam night vibe, so to say. This is what Bazarov’s father saw when he looked in his son’s eyes, this is what Rashid’s father saw when his son left the village to study sciences and become an engineer, this is what Russia sees every day when she looks into the mirror, this is what Fäil also saw looking at Rashid, and, even though the metaphor doesn’t stretch to apply to them two, the idea for the cover was born.

In addition to translation, we are lucky to have remnants of Huzin’s notes which unfortunately remain largely fragmentary and only in Tatar. But judging from the scarce commentaries I found online, there are some substantial changes in a few places in the novel, such as the dialogue that described what nihilism employed the same imagery as on the cover (here provided in English):

A nihilist is a man who shows a kukish to any authority, who does not take any principle on faith, whatever reverence that principle may be enshrined in. […] There used to be Hegelists, and now there are Figelists. […]

The foreword explained this idea as well — a son is one who shows a kukish to his father and a father is one who shows a kukish to his son; each is to the other an unfathomable book, and the kukish is that missing bridge between generations, the crux of the whole parents vs children and past vs present flux. Being a mathematician, Rashid couldn’t resist adding that a father and a son are, in fact, variables, that can be substituted with many things, such as an individual and an authority, communism and, well… whatever or whoever is on the other side of it. This philosophical flexibility extended even to his translation of the title itself as Rashid accurately chose “Atalar” (fathers-ancestors) rather than just “Ätilär” (fathers-dads). The choice of Balalar (children) was obvious, for it’s the literal translation and intended meaning of the original title “Отцы и Дети”, which in English would be best rendered as “Fathers and Сhildren” unlike how it’s known. The authority, famous for its vice and powerful grip and advanced censorship tactics, wasn’t particularly happy with the sentiment. The Bazarovian inevitable descent into the void, on which Huzin enthusiastically elaborated, wasn’t, so to say, compatible with the bright communist future that was to come.

It was foolish to campaign for their own Tatar alphabet, be it Arabic or Latin-based, the former being more accurate and flexible, as Huzin believed and briefly mentioned in the commentary as well, so foolish that he never did campaign. And it was foolish to assume a drunken joke would be understood by a university censor as indeed a joke and not an anti-Soviet statement. The book “Atalar häm Balalar” with the primordial amphibious father surrounded by a circle of figs on the cover was seen as an insult to Stalin himself, as the censor hinted, even though he never stated it directly. Huzin, of course, defended himself, saying that it is indeed not the primordial father; it’s not primordial and it’s not a father, moreso, as he aptly described, “father” is a variable with quite wide distribution and can be anything, including the bourgeois, capitalism, or Tsar, and a kukish can be used to ward off an evil eye, so it couldn’t be clearer. It could, however. The symbolism itself wouldn’t be appreciated by the Father who favoured socialist realism. Although “Atalar häm Balalar” was indeed a prime example of realism that seemed social enough, yet perhaps not so socialist, the general aura of the book didn’t appeal to the censors and then to the university authorities and both Huzin and Fatihov were voluntarily moved to Siberia, where they first worked as engineers, and later, when the Second World War started, shared the fates of many on the Far East front.

The publication of what could have been a revolutionary translation for its time never happened, but the original survived and Huzin’s interpretations managed to endure. We can only honour his vision and project it onto the tendencies of modernity when the essential intergenerational flux is seemingly broken, when there are still figs and kukishes demonstrated all around: to refuse comprehension, to insult, and to ward off evil eyes, but instead of continuity, there’s a set of discrete categories, when some want to swim in the primordial pond, some want to drink it, some want to dry it out, everyone thinks they are indeed the best generation, and no one actually understands who they are in the set of two variables — fathers and sons.

The fig gesture appears across Mediterranean, Slavic, Turkish, and Asian cultures with varying meanings: warding off evil, sexual insult, or mocking refusal. In Europe, its roots go back to ancient Roman ritual, where the manu fica was used to ward off the spirits of the dead. The same hand shape appears in medieval Christian art as the manus obscena, and the Ancient Greek word for “sycophant” may derive from “one who shows figs,” referring to insulting false accusations. The meaning can range from explicitly sexual, even an invitation, to innocent childish play.

Liked without reading. Will read later.

In the U.S. this gesture means "Got your nose." You pretend like the thumb is the other person's nose and then put it on your own face. Maybe says something about our culture.