What Is the Oldest Russian Book?

a bit of history that turns into a bit of poetry that turns into a bit of politics

Dear wanderer,

While I'm currently on a bit of a writing hiatus, I'm pleased to share a guest post by my friend, fellow writer, and member of the Soaring Twenties Social Club, Konstantin Asimonov. His Substack is always at the top of my reading list, and I highly recommend you check it out.

Today's article presents a curious investigation into the historical depth of Russian literature and offers a subtle yet astute commentary on its inherent and persistent characteristics. It's a great fit for Nova Nevédoma's ethos and themes, and I'm sure you'll enjoy it if you haven't had the chance to read it before.

Until soonly soon,

Vanya

This post is dedicated to the memory of Alexei Navalny.

What is the oldest book written in Russian? Or, rather, in proto-Russian, in Old Slavic? I dove into Wikipedia with this naïve question. As with any other diving expedition, this one did not guarantee results and started somewhat boring, but in the end, it did not disappoint.

What is the oldest Russian book? That seems like a simple question, right? For a while, I thought the oldest book written in Russian was ‘The Tale of Igor’s Campaign’, an epic poem in Old Slavic that is quite widely known and even taught in schools (and, as I learned just now, translated to English by Nabokov). It is fairly old: it is describing an event that occurred in 1185, and the poem itself is probably contemporary. However, the only existing manuscript of the ‘Tale’ is dated to the XV century, which created some controversy around it. This story is fascinating in its own right, but it is not the focus of this letter, even though it shares the same hero, a star of Russian linguistics, professor Andrey Zaliznyak. We will encounter this name again, but for now, let’s ask ourselves: how can a book this old even be preserved?

This, you see, is a question for a chemist.

The oldest preserved documents we have are stone and clay tablets. In fact, if you want your Substack archive to exist for thousands of years, stone or clay are still your best bet. Clay and limestone that were so successfully used for this purpose by our ancestors were abundant in Iran, Egypt, Turkey, all around the Mediterranean, which is why we know so much of Mesopotamian and Egyptian cultures. You can also try writing on metal, but it might be even more hustle, plus it’s hard to edit. This is, overall, not an efficient way to store information; the thickness-to-useful area of a stone tablet is even smaller than that of an old Palm PDA handheld computer.

Papyrus (not the font!) is also a great solution; it will preserve your writings for thousands of years as well. However, if there is not a single reed of Cyperus papyrusgrowing near you, you might have two main options left: parchment and paper. These were more widely available to denisens of Northern Europe, but they were still extremely expensive. Also, on those particular materials, one has to think not only about the preservation of the substrate but also about the preservation of the inks, which are likely to fade away quicker than the decomposition of the material. Beware: modern office printer stuff will not last that long.

The oldest surviving parchment Russian book is the so-called ‘Ostomir Gospels’, an absolutely beautiful illustrated manuscript written in 1056–1057 for a Novgorod governor named Ostomir. Being a present to the ruler, it was extremely well preserved. You can check out some examples of Ostomir Gospels’ illustrations on Nicholas Kotar’s website.

As expected, if you look for old parchment books, you will find exclusively religious texts. The material was expensive, and closters were medieval epicenters of literacy, after all. But were they the only literal people in Russia during that period? Of course not, but to find them, we need to let parchment go.

An alternative, and I assume, more affordable material, that was used by those who lived in Slavic countries is the same thing that makes modern Russian expats shed a tear each time they encounter it in a forest: a birch tree. The internal side of its bark is soft and light-colored, which makes it suitable for writing. No inks were used; the manuscripts were basically scratched on the bark with a metallic stylus. The best practice, however, was to cover them with an additional layer of wax; that allowed better indentation and, maybe more importantly, allowed for reusing them, making birch bark manuscripts even more affordable to common people.

Birch bark is not a very long-living material. Luckily, it survives quite well in an oxygen-depleted atmosphere. Archaeologists have found around a thousand such documents, preserved in a specific deep clay layer, found in Novgorod and many other towns in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. These manuscripts were analyzed and organized by Andrey Zaliznyak, who developed a whole linguistic method of dating them when stratigraphic dating was not applicable.

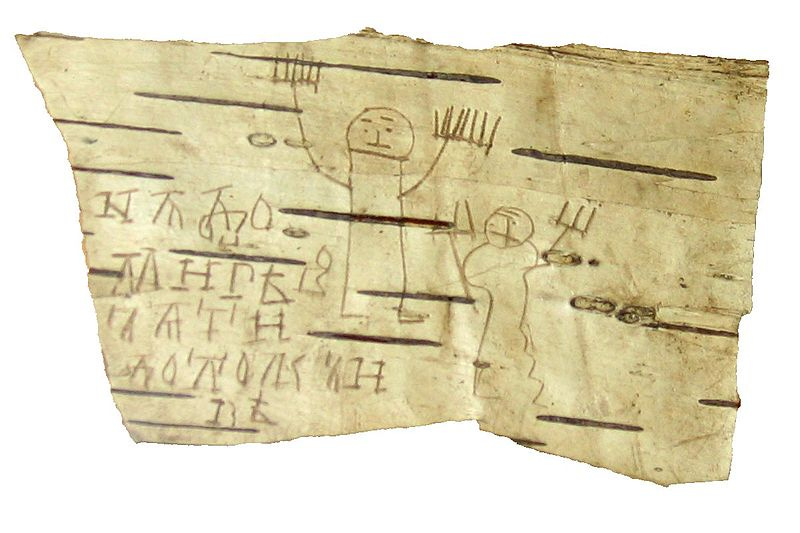

The amazing thing about the birch bark manuscripts is that, due to their relative low price, they were used in everyday life and, as such, are more fascinating to read than yet another variation of the gospel. My favorite is a collection of seventeen short pieces of bark, all written by the same boy, a 6- or 7-year-old Onfim. These seem to be his school notes; most of them have an alphabet, some numbers, or a few phrases from the Psalms. Many of them also feature his drawings: of a knight on a horse, a wild beast, or Onfim himself with his friends. We know that because he actually signed them.

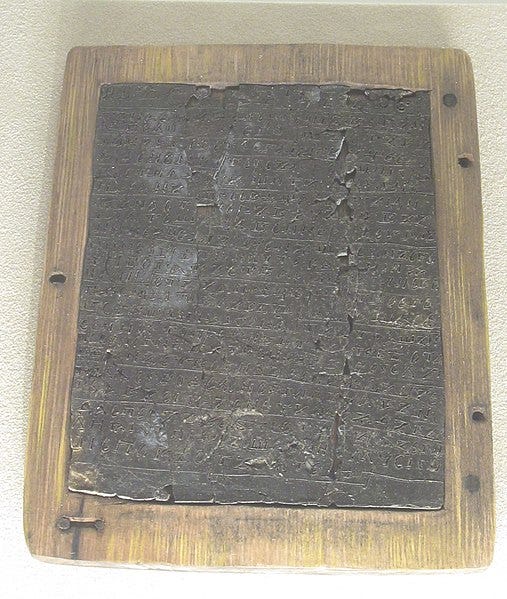

These, however, are not real books; they are more like letters, notes, and business papers. But there is an actual book written using the same technique as well. It’s called ‘Novgorod Codex’, and it’s strictly speaking not bark but tablets of soft wood coated with wax. It was unearthed in Novgorod in 2000, and currently it is considered to be the oldest book of Kievan Rus. The top wax layer (‘the basic text’) contains several psalms. But the most interesting thing is beneath the obvious.

To preserve and study the wax layer, it was carefully detached from the wood. That’s when it turned out that the wood tablets, made out of soft linden, were scratched through the wax by not only the latest but also the previous writings. It’s hard to imagine the staggering amount of work that was put into discerning and then deciphering the separate letters in the separate layers of ghosts of old texts. It wouldn’t be a surprise that this work was done, largely, by the very same Andrey Zaliznyak.

This, as Zaliznyak calls it, “hyper-palimpsest”, this labyrinth of overlaping scratched letters, is, to this day, the oldest book written in Russian. As opposed to the top layer, it is very unusual. There are some personal prayers there, some marginal notes, some copybooks, even some translations of even more ancient texts. But what completely captured my heart was a poem. It was probably written by a monk named Isaacius, who probably should be considered the first Russian poet. And boy, did he set a high standard! Here is the poem in its entirety:

The world is a city in which the church interdicts heretics. The world is a city in which the church interdicts the unwise. The world is a city in which the church interdicts the disobedient. The world is a city in which the church interdicts the innocent. The world is a city in which the church interdicts the blameless. The world is a city in which the church interdicts the unbending. The world is a city in which the church interdicts those undeserving of such punishment. The world is a city in which the church interdicts those undeserving of interdiction. The world is a city in which the church interdicts those of the purest faith. The world is a city in which the church interdicts those worthy of praise. The world is a city in which the church interdicts those worthy of glorification. The world is a city in which the church interdicts those who have not deviated from the true faith of Christ.

I was stunned to read this text and heartbroken to realize that nothing ever changes.

After reflecting on that, I managed to see some hope in the fact that the first found text in Russian is an anticlerical, rebellious poem. All this talk about cultural DNA is probably gobbledygook, but Russian culture is still very literature-centric. Knowing something about its history, I can find such rebels and poets in every century, under every regime, even the most cannibalistic ones. They were often alone, but they were never fully exterminated.

After a poet dies, another one takes their place.

There are two main takeaways for me from this mini-research into the roots of my own culture. First, a reminder that the history of the Russian people is a history of oppression and violence. Almost always, it was auto-oppression, internal oppression, oppression by the same exact people. It permeates Russian culture like an autoimmune disease. And oppression leads to trauma. A sad, sombering thought, but a relevant one. This is why dumb pop songs may turn into war songs in a blink of an eye.

The second takeaway is a more general one. Our culture, any culture, is shaped by the words we write but also by the materials that we use. On the one hand, in order to preserve our words, we really need to think about the medium we write them in. Using the wrong materials may result in our times being called something like ‘The Dark Ages’ by the historians of the future. And on the other hand, imagine how many poems were lost, how many poets were never known because of the unrelenting processes of rot, decay, and oxidation?

P. S.

This letter was written before I learned about the death of Alexei Navalny in an Arctic prison. I still decided to originally post it on the day the world learned of his death because I found it strangely relevant. Indeed, the world is a city in which the state kills those who fight tyranny and say the truth.

Thanks for sharing this, it was so enlightening and thought provoking !

Totally fascinating (and clearly written). I have shared it with the Russian half of my family. Thank you for posting