Rodin's Hands Through Rilke's Eyes

poetry, sculpture, bodies and bodylessness (among other things, or a lack thereof)

In 1902, a young poet Rainer Maria Rilke met the renowned sculptor Auguste Rodin after taking up an assignment to write about Rodin's work, an assignment that happened to evolve into artistic mentorship and transform Rilke's poetry. After their initial meeting in September 1902, Rilke spent four months observing Rodin's studio work, Three years later, in September 1905, Rilke became Rodin's secretary, living at his country estate and organising his correspondence. Though Rodin fired Rilke in April 1906 over a misunderstanding about a letter, they reconciled in 1908 when Rodin visited Rilke at an artists' commune in Paris, whither he later moved himself. The commune’s building would eventually become the Musée Rodin after the sculptor's death. Those years of their artistic exchange were profoundly influential for both of them, especially for the young poet.

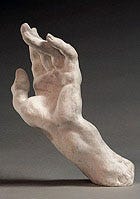

During his time in Rodin's orbit, Rilke became especially captivated by the sculptor's treatment of hands. Rodin created hands that existed as isolated and complete body-less sculptures, each with its own story: sleeping, grasping, pleading, grabbing, caressing, expressing despair, reaching for something greater—all with such muscular tension that they seem about to tear themselves apart.

I found out about this story reading an excerpt from the book "The Question of the Thing" (2016) by Soviet and Russian anthropologist and literary critic Valery Podoroga. In that excerpt, which are sections 47-52 of the whole book, Podoroga analyses Rilke and Rodin’s relationship and examines what he calls the "incredible and ever-present plasticity of Rodin's hands". Podoroga suggests that Rodin's fascination with hands began with his attempt to understand his own hands and to express their full potential in sculpture. Podoroga writes that the hand in Rodin's work becomes "the sole bearer of gesture, whose vector determines the movement of the entire body." The hand, he writes, precedes both thought and word as the main means through which we forge meaning; the hand, he writes, is how we engage with craftsmanship and through that build physical relationship to the world. In those sections, Podoroga uses poetic observations from Rilke’s book “Auguste Rodin” with philosophical concepts about how objects ("things") acquire significance through human touch and intention, discusses Heidegger’s philosophy and a bunch of other interesting things, but that’s later (perhaps). If there’s interest, I can translate excerpts from those sections of Podoroga’s book and share them with my commentary as a potential Part II for this post. In this post, I only want to share some of Rilke’s observations accompanied with pictures of Rodin’s works. I believe they are wonderful, profound, or at least curious, reflections of these remarkable sculptures.

So, Rodin’s hands through Rilke’s eyes (well, and words).

"Things. When I pronounce this word (do you hear?), silence reigns – the silence surrounding things, all movement has settled, turned into contour, the past has closed with the future, and duration has emerged; space, the great pacification of things that have nowhere to hurry."

"Among Rodin's works, there are hands – isolated, small hands, belonging to no body and yet alive. Hands rising up in angry irritation, hands bristling with five fingers which seem to bark like the five throats of a hellhound. Walking hands, sleeping hands, awakening hands, treacherous hands, hands burdened with hereditary vice, and tired hands, no longer wanting anything, lying somewhere in a corner like sick animals that know no one will help them. But hands are a complex organism, a delta where much life flows from afar, pouring into the great stream of action. Hands have a history, in fact they also have their own culture, their own special beauty; they are granted the right to their own development, their own desires, feelings, whims, and preferences."

"In his memory, gestures arose – gestures of refusal, farewell, renunciation. Gestures after gestures. He collected them. He formed them. They poured forth to him from the depths of his knowledge."

"...Rodin possesses the power to endow a certain part of this vast undulating surface with the abundance and independence of a whole, hence that unprecedented interconnection of figures, that cohesion of forms, that inseparability despite everything."

"One walks among these thousand forms overwhelmed with the imagination and the craftsmanship which they represent, and involuntarily one looks for the two hands out of which this world has risen. One thinks of how small man's hands are, how soon they tire, and how little time is given them to move. And one longs to see these hands that have lived like a hundred hands; like a nation of hands that rose before sunrise for the accomplishment of this work."

"A hand laid on another's shoulder or thigh does not any more belong to the body from which it came,—from this body and from the object which it touches or seizes something new originates, a new thing that has no name and belongs to no one."

"From Dante he came to Baudelaire. Here was no judgment, no poet, who, guided by the hand of a shadow, climbed to the heavens. A man who suffered had raised his voice, had lifted it high above the heads of others as though to save them from perishing."

I love these posts. I'm a sucker for artist biography, especially those that detail relationships between artists. So fun!

Very interesting essay about both artists. I love Rilke's poetry and Rodin's sculptures. I remember how I was surprised by his Balzac. Usually, an artist finds something attractive in his model. His Balzac (to me) was almost disgusting in Roden's realism of Balzac's body, huge fatness, eyes, and even his expression. Actually, it was real Balzac. It was a work of genius

Rodin.