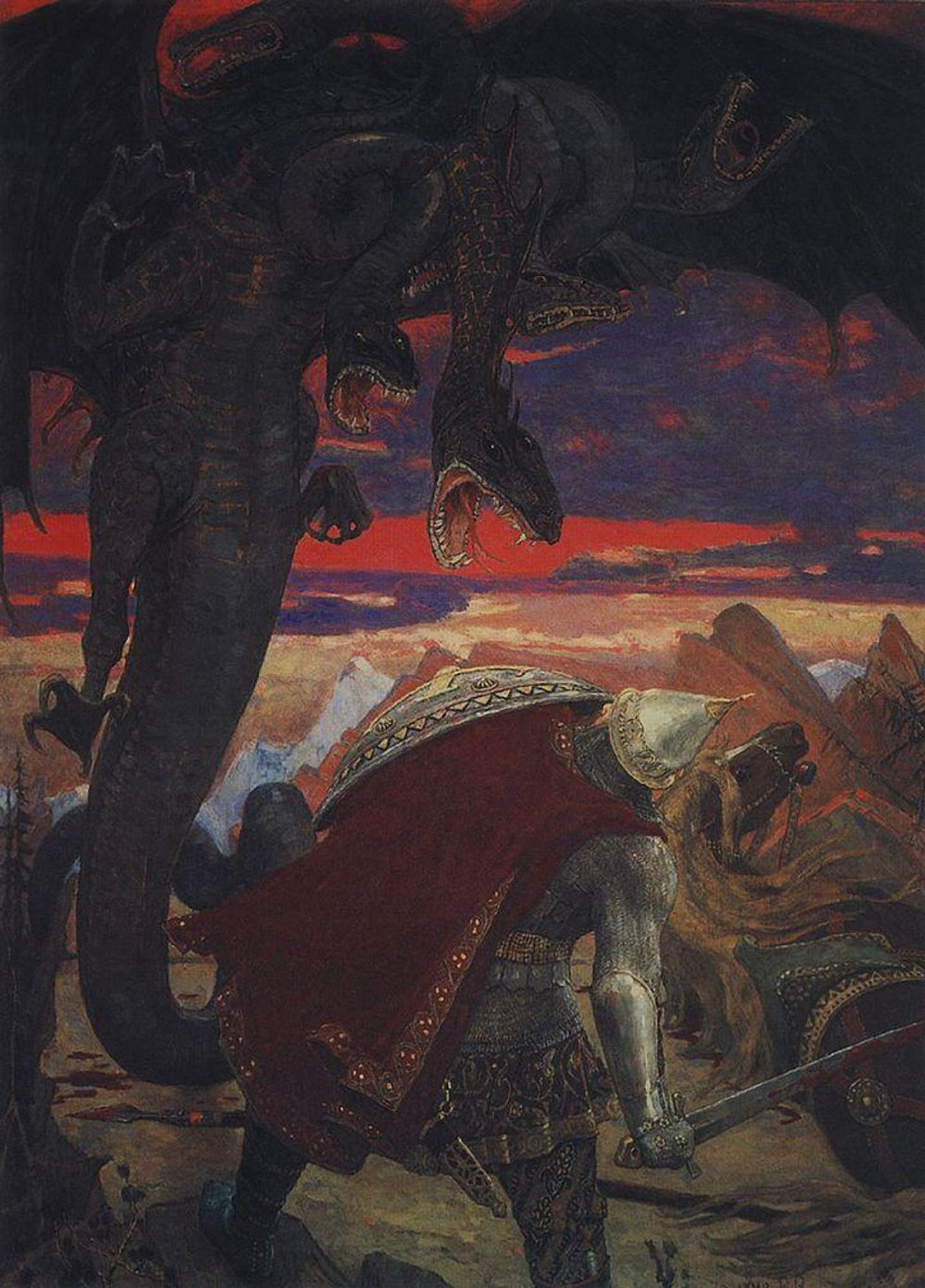

What is a dragon? Not in a biological sense but in essence, as an archetype. In fairy tales and myth lives on an image of a dragon tyrant, a powerful, invincible creature with oppressive demeanour that demands regular endowments of gold coins and beautiful maidens. A village or a country living under the dragon's reign doesn't question his power, or if they do, they have no idea how to beat him and free themselves from him. Some cower before the dragon, some love him, some respect and thank him for the protection and—though not much—food and resources the dragon provides his serfs, leftovers from the Tsar's plate. They may even "elect" the dragon themselves because, well, many are so accustomed to him and they believe that should the dragon be gone, even darker times would descend on the world. The dragon becomes an unattainable element of reality and the suffering and oppression he inflicts on the populace becomes perceived as evil necessary to maintain a life of stability if not prosperity, a shallow and poor life that without that necessary evil can metastasise into something far worse than it already is. Therefore any dragon's action is justified.

At one point, archetypically or dialectically, there appears a hero, a heretic, a rebel, a knight, a prince from the faraway land who impugns the dragon's regime and validity of his power and aims to overthrow the creature and free the townspeople to lead them to the better, brighter future, where there's no dragon, no racket, no sacrificed virgins and everything is tiptop splendorous. The heretic-hero sees the dragon as the main and the only problem and by his logic, when the dragon is gone, the problem is gone. But is it really enough to kill the dragon? What is that precisely which is going to be killed?

In Evgeny Schwartz's play "The Dragon", we find a rather bleak and sore answer. The play is a fairy-tale which you could categorise as literature for children. Like other authors in a similar genre, "a political fairy-tale", Schwartz went to it to potentially escape censorship, for any serious adult political work not directly praising communism would have had a higher likelihood of being censored, banned or even, were its author unlucky enough, become a reason for repression. Many Soviet artists used the medium of children's literature as a hideaway from censorship, hence—my guess—we see so many weird, traumatising, deeply serious, sometimes psychedelic works in seemingly innocent stories and animation made for children. It was easier to interpret the collisions into which the fairy-tale characters fell, and it was easier to interpret them in an innocuous sense and to divert suspicions of anti-government intentions from the authors. It didn't, of course, guarantee safety, nor did it, of course, guarantee a piece of art its existence.

"The Dragon" was censored and didn't make it to stage for many years. The play was written during WWII while Schwartz was in evacuation in Stalinabad, now Dushanbe. The first attempt to perform it happened in Leningrad during the war, then in Moscow in 1944. Despite the play getting a green light after the previews, it was immediately prohibited to show after its first public performance and didn't see stage in USSR for 18 years, until 1962, but even then, after 17 performances, was banned again. Despite that, "The Dragon" was performed in many theatres across Europe, including Poland and Germany. Only during Perestroika did the play return to Soviet stages and was even made into a film.

According to some, Schwartz began writing "The Dragon" as an allusion to Hitler's Germany, but the brief intensification of Russian-German friendship, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, destroyed any chance of publication or staging. If the dragon at home remained too dangerous to even contemplate, the foreign one had suddenly become an ally and an open theatrical statement ceased to be possible. Though only for a few years. After that, when the war started and the play was completed, it could be unequivocally defended as anti-fascist. Schwartz himself claimed that the dragon's three heads represented Hitler, Goebbels and Ribbentrop. However, the problem and the drama extended beyond the dragon itself and it didn't help.

Ironically, some generalised form of fascism depicted in "The Dragon" was taken rather personally in Soviet Union.

"The Dragon" is a story of a town ruled by a cynical, vile, yet "homely" tyrant for almost four centuries. The dragon archetypically imposed an annual virgin tax on the town. Every year he picks one young woman and takes her to his cave after which nobody sees her. Lancelot, a hero who arrives in the city, is disgusted by the direness of the predicament and with utmost immediacy decides to liberate the city. As he learns from Cat (yes, it's a fairy tale, having a talking cat is a must), people don't just not meow against but smile when it's time to give away their daughters to the dragon. They describe the town as a quiet place where nothing happens, which also shocks Lancelot.

Lancelot: And... what about the dragon?

Charlemagne: Oh, that... But we're so used to him. He's been living here for four hundred years.

The belief that the dragon can't be defeated is so deep that it's beyond contemplation.

Lancelot: Why?

Elsa: Because there's nothing to be done about it.

<...>

Lancelot: Forgive me, just one more question. Has really no one tried to fight him?

Charlemagne: Not in the last two hundred years.

All townspeople, including the taken daughters, are humble about their fate. From the first minutes, the play shows us the evolution of ordinary people who once became hostages of tyranny and now are a part of it.

What makes "The Dragon" unique and timely, both for 1930-1940s, beyond, and for 2020s, is it's not about oppression, violent power, or life in darkness, but about the society in a state of an impregnable panopticon, where no oppression nor violence is required to ensure obedience. The characters of the play—except the dragon himself and his new nemesis Lancelot—are disoriented, intimidated by the mere notion and possibility of terror, and by their denunciations contribute to the tyranny and ultimately take the repression for granted.

Lancelot: So—forgive me for asking again—does no one even try to stand up against the dragon? Has he become completely shameless?

Charlemagne: No, not at all! He's so kind!

Lancelot: Kind?

Charlemagne: I assure you. When our town was threatened by cholera, at the town doctor's request, he breathed his fire onto the lake and boiled it. The whole town drank boiled water and was saved from the epidemic.

Lancelot: When was this?

Charlemagne: Oh, not long ago. Only eighty-two years ago. But good deeds are not forgotten.

For me, it was hard to believe that it was written almost a century ago, given how accurately it depicts the present. You might've guessed what and whom I'm alluding to (obviously so). You needn't be a scholar of politology and sociology to see all the parallels Schwartz draws. Somehow, reduced to archetypes and ofttimes absurd comedy, "The Dragon" is even more relevant to the present time than it is to the past century, as if the play was used as a playbook by modern regimes. That is, however, not a coincidence or a prophecy—like with many similar literary cases aimed to expose societal issues—not even a self-fulfilling prophecy, but just the author's observant and surgically accurate view on those issues.

The dragon's regime in the play ticks all of the boxes of fascism as defined by Umberto Eco: cult of tradition, rejection of modernism, action for action's sake, disagreement is treason, fear of difference, appeal to frustrated middle class, obsession with plot, enemy both strong and weak, pacifism is trafficking with the enemy, contempt for the weak, everyone educated to become a hero (or ironically inverted—educated for submission), machismo, selective populism, newspeak. All of which you'd easily see yourself when reading the play, or probably have seen around you lately.

The regime, of course, has its own enemies of the state:

Charlemagne: They are vagabonds by nature, by blood. They're enemies of any state system—otherwise they would have settled somewhere instead of wandering to and fro. Their songs lack masculinity, and their ideas are destructive. They steal children. They infiltrate everywhere. Now we're completely cleansed of them, but a hundred years ago, any dark-haired person had to prove they had no gypsy blood.

Lancelot: Who told you all this about the gypsies?

Charlemagne: Our dragon. The gypsies brazenly stood up against him in the first years of his rule.

Lancelot: Brave, impatient people.

And later:

Dragon: Are you a descendant of the famous wandering knight Lancelot?

Lancelot: He is my distant relative.

Dragon: I accept your challenge. Wandering knights are just like gypsies. You need to be destroyed.

The dragon, of course, sees himself as superior to the townspeople:

Dragon: <...> You won't find such people anywhere else. My handiwork. I tailored them. <...> You see, my dear fellow, I personally maimed them. Maimed them exactly as required. Human souls, my dear, are very tenacious. Split a body in half—a person will die. But tear a soul apart—it just becomes more obedient, that's all. No, no, you won't find such souls anywhere. Only in my city. Armless souls, legless souls, deaf-mute souls, chained souls, police-dog souls, damned souls. Do you know why the burgomaster pretends to be mentally ill? To hide the fact that he has no soul at all. Hollow souls, corrupt souls, burned-out souls, dead souls. No, no, it's a pity they're invisible.

When Lancelot tries to reveal that to them, in particular Elsa, a girl to be taken next by the dragon, she's terrified to admit it:

Lancelot: The dragon has dislocated your soul, poisoned your blood and clouded your vision. But we shall put all this right.

Elsa: Don't. If what you say about me is true, then I'd better die.

The life they've been living is deemed the only possible right version of life, as townspeople are brainwashed to think, and other life is not possible, even death would be better. They dismiss any uncomfortable thought in such direction as soon as it appears in their heads:

Heinrich: Now tell me the truth...

Burgomaster: Oh come now, my little son, what's all this about truth, truth... I'm not some common townsman, I'm the burgomaster. I haven't told myself the truth for so many years that I've forgotten what it even looks like, this truth. It makes me sick, throws me back. You know what truth smells like, the cursed thing? Enough, son. Glory to the dragon! Glory to the dragon! Glory to the dragon!

All that's left for their poisoned souls is to chant "Glory to the dragon!", for it's the mantra that keeps their reality intact. Apart from Lancelot, only children, with yet innocent and unspoiled minds, dare to question the dragon's power:

Boy: Mummy, who's making the dragon run away across the whole sky?

All: Shhh!

1st Townsman: He's not running away, boy, he's manoeuvring.

Boy: Then why has he tucked his tail in?

All: Shhh!

1st Townsman: The tail is tucked in according to a pre-planned strategy, boy.

<...>

Boy (pointing at the sky): Mummy, mummy! He's turned upside down. Someone's hitting him so hard that sparks are flying!

All: Shhh!

Boy: Mummy, why is it harmful to watch him being beaten?

All: Shhh!

<...>

Heinrich: Listen to the communiqué from the city's self-government. The exhausted Lancelot has lost everything and has been partially taken prisoner.

Boy: What do you mean, partially?

Heinrich: Just that. It's a military secret. His remaining parts continue to resist in a disorderly fashion. Incidentally, the honourable dragon has discharged one of his heads from military service due to illness, with its transfer to the first-tier reserve.

The little boy appears as a voice of reason, but he's too powerless to oppose the adults. As he says to Lancelot: "I would stand up for you, but mother is holding my hands."

Despite the townspeople's attempt to weaken Lancelot, provide him with faulty equipment, and hide the details of the battle, the dragon is defeated. At the same time, Lancelot disappears, curtains fall and we're welcomed to Act 3 to witness consequences of the regime’s fall only to realise that few things have changed.

The townspeople "elect" a new leader, a president, through a sham election, a parody of a democratic process. The Burgomaster simply steps into the power vacuum, using the same methods of control as the dragon did. We see the same process unfolding for years in authoritarian regimes—either direct descendants take the "throne" or others become dragons themselves.

Burgomaster: What's happening in the city?

Jailer: Quiet. Though they're writing.

Burgomaster: What?

Jailer: Letter 'L' on the walls. That stands for Lancelot.

Burgomaster: Nonsense. The letter 'L' stands for 'Love for the President.'

Jailer: Ah. So we shouldn't arrest those who write it?

Burgomaster: No, why not? Arrest them. What else are they writing?

Jailer: Shameful to say. 'The President is a beast.' 'His son is a crook...' The President (chuckling in a bass voice)... I dare not repeat how they put it. However, mostly they're writing the letter 'L'.

The new president doesn't just preserve a power structure, but legitimises it with various bureaucratic forms, and moreover, keeps "the virgin tax", forcing Elsa to marry his son Heinrich, which prompts her poignant monologue:

Elsa: My friends, my friends! Why are you killing me? It's frightening, like in a dream. When a robber raises his knife above you, you can still escape. The robber will be killed, or you'll slip away from him... But what if the robber's knife suddenly lunges at you by itself? And if his rope crawls towards you like a snake to bind your hands and feet? If even the curtain from his window, that quiet little curtain, suddenly also lunges at you to gag your mouth? What would you all say then? I thought you were all just obedient to the dragon, as a knife is obedient to a robber. But you, my friends, it turns out you are robbers too! I don't blame you, you don't notice it yourselves, but I beg you—come to your senses! Could it be that the dragon didn't die, but, as often happened with him, turned into a human? Only this time he transformed into many people, and now they are killing me. Don't kill me! Wake up! My God, such anguish... Tear apart the spider's web in which you're all entangled. Will really no one stand up for me?

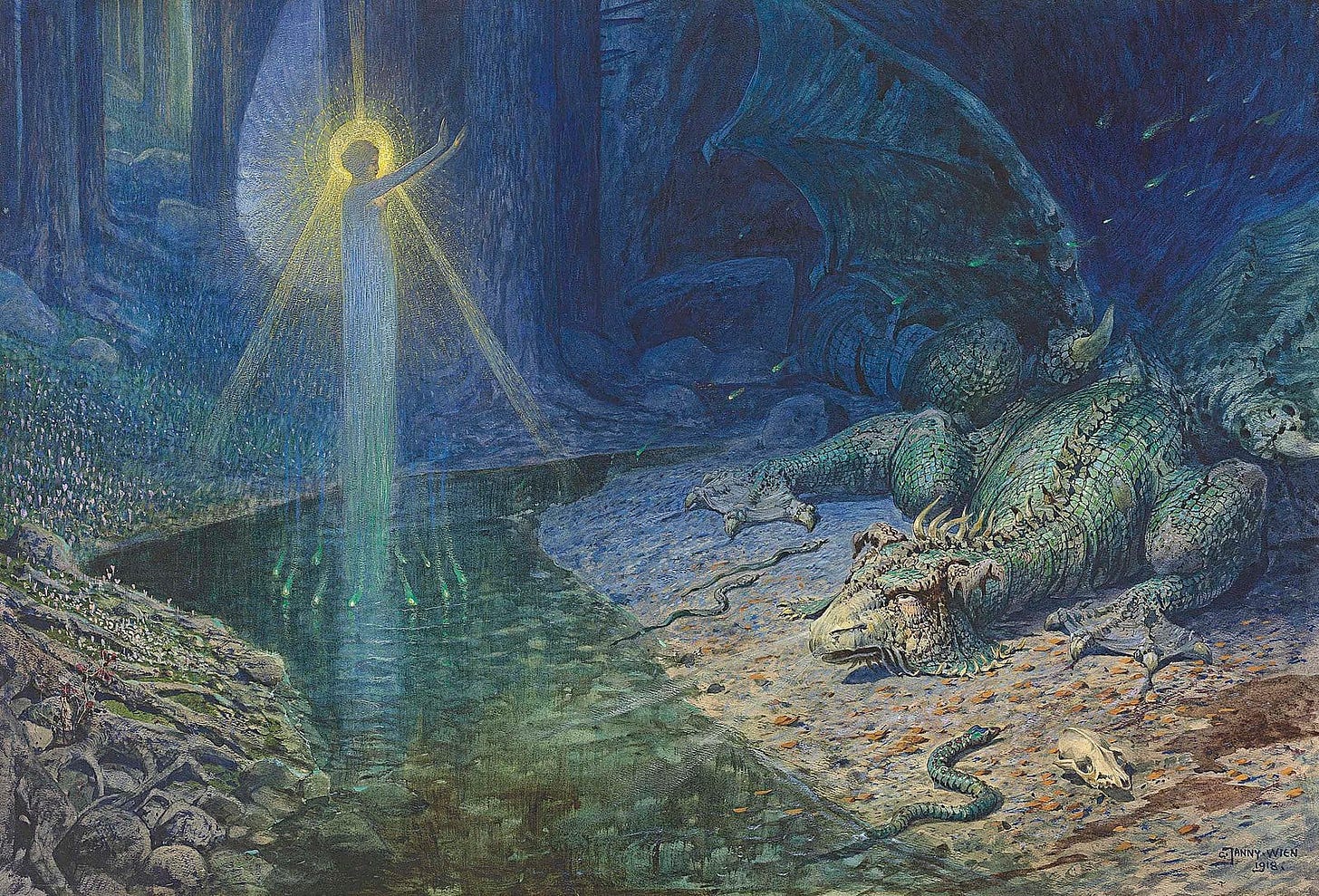

The dragon, an individual dictator, remains in history as a mere embodiment, a conduit of psychological structures of oppression that he built over the first years or decades in power. Those structures won't just go away in a snap of fingers, snap of someone's neck in a rope or under the weight of guillotine. "The Dragon" illustrates that phenomenon. The authoritarian system doesn't fall in a moment, the world doesn't pivot and strive headlong to the bright future, no, the system keeps living in people's minds. In the present historical context, this idea terrifies more than anything. When will it end? Will it ever end?

One of the stupidest and most cynical sayings in the history of political thought is that "every country has the government it deserves". It's simply a wrong and oversimplified view of extremely complex social and political dynamics and, well, victim-blaming on a national scale. But it also ignores the cause and effect. In the dragon example, the egregore of fascism lives on virally as an autonomous entity arising from the collective consciousness (and conscience) after it has been implanted there by years of violent threats, oppression, propaganda, and brainwashing. It shapes the populace's minds to fit the image of the draconian leader by justifying his existence. Thus the most dangerous damage done by the dragon is one done to the minds.

There are, in fact, two battles and two dragons: one who sits on the throne, ofttimes wobbly; and one who like a weed sits in people's minds. Once the first battle is won, the second battle begins.

Should we ignore it, we will let the dragon live in the dungeons of mind manifold for years to find a chance to manifest himself anew.

Lancelot: "The work ahead is meticulous. Worse than embroidery. In each of them, we'll have to kill the dragon. <...> I love all of you, my friends. Otherwise, why would I bother with you? And if I do love you, then everything will be lovely. And after long troubles and torments, we'll all be happy, finally very happy!"

Curtains.

Thank you for your time! My recent book “Deleted Scenes from the Bestselling Utopian Novel” also explores the psychological toll of tyranny, how ordinary people try to survive in the opressive world (or ignore it). It is my best and most personal work to date.

"Deleted Scenes" is a surreal, experimental dystopian narrative set in the remote, snow-covered island of Novo Tsarstvo, uncanny reflection of contemporary Russia. Through a mosaic of perspectives, the author explores the lives of ordinary people struggling under a totalitarian regime where reality blends with nightmares. The novel combines psychological horror with dark humour to examine themes of truth, violence, and freedom, while showcasing the resilience of the human spirit in the face of oppression.

Should you be interested, the book is available worldwide as softcover, hardcover, or ebook at all major retailers, including Amazon, Blackwell (discounted price!), Waterstones (UK), Foyles (UK), Barnes & Noble (US), Hugendubel (DE), Kobo (ebook).

If you want to read the book but have any trouble getting hold of a copy, including financial, please reach out to me. I'll do my best to help!

To get a taste of the book, you can read one of the stories, "Dream", for free in the Soaring Twenties magazine.

So, what’s the second battle? The process of healing everyone’s souls to become like Lancelot’s?

To freely love and become their own dragon slayer? Do we end there because making everyone not into an asshole is its own complicated journey that likely deserves its own narrative?

I enjoyed your writing and interpretation of this - honestly makes me want to see the play or at least read it. It however has left me with so many questions, which maybe is the point.

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/D/bo28433434.html

Have you read this book?